20 of the most game-changing British tech breakthroughs

One area where Britain has always been Great is innovation and invention – and here are the very best of the best

It might seem like the Far East and the USA are where the biggest tech breakthroughs are being made these days, but it wasn’t always that way. From the Industrial Revolution to the computer, Britain has been a world leader in innovation for a sizeable portion of modern history. And we’ve scoured the archives to bring you 20 of the most important breakthroughs made by British brainboxes.

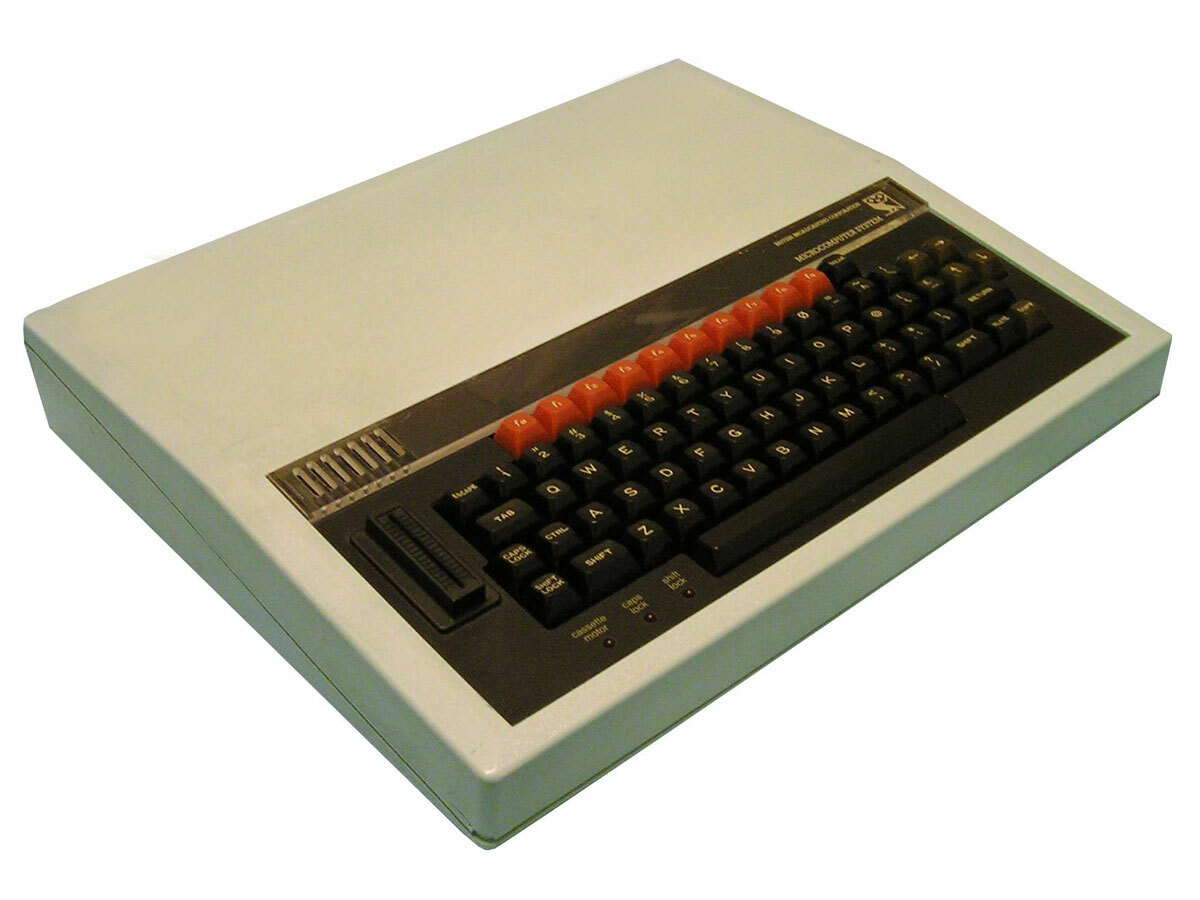

ARM chip

Developed by Cambridge-based Acorn in the early 80s and debuting in the BBC Micro, the Acorn RISC Machine processor – or more precisely its streamlined architecture – has revolutionised modern computing and mobile technology. ARM-based chips are used in the iPhone, iPad, Samsung Galaxy Note 3, Samsung Galaxy Gear and so much more: in 2010, ARM-based CPUs held a staggering 95 percent share of the smartphone market. And by 2015, ARM predicts that over half of all tablets, mini-notebooks and other mobile PCs sold will run on its architecture.

READ MORE: Stuff Hall of Fame: Acorn Archimedes, the original ARM computer

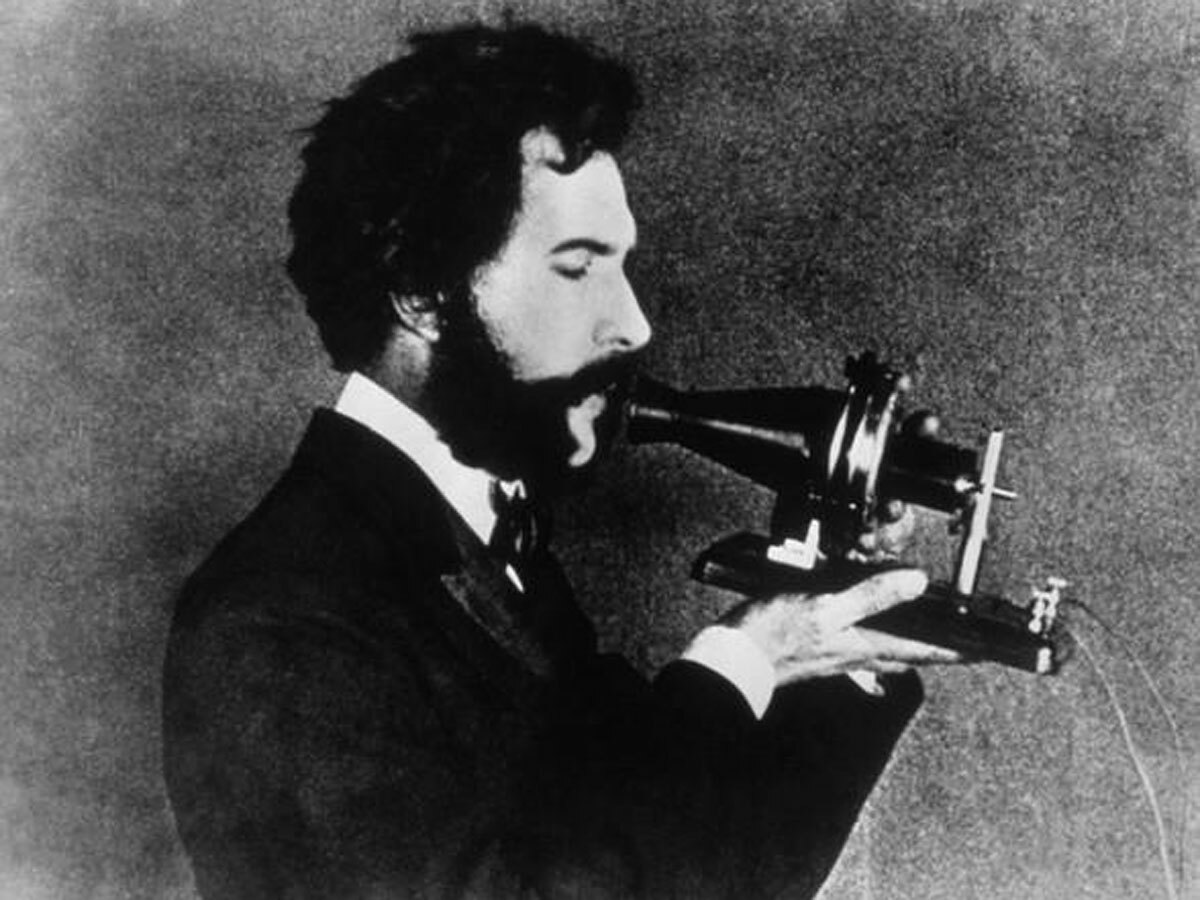

Telephone

Doubtless Scotland’s most famous invention since haggis, Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone is a controversial one – because many people maintain that he "stole" the idea from American inventor Elisha Gray, or at least came up with it later.

Whatever the truth, Bell succeeded in getting the patent in 1876, and the rest is history. And there’s no denying he was a scientific genius, racking up patents for the photophone and wax phonograph, and creating an induction balance metal detector – in a bid to save the life of US President James Garfield from an assassin’s bullet.

Bell’s mind would’ve been well and truly boggled by modern smartphones, but his telephone was the starting point. Oh, and Gray is generally credited with inventing the music synthesiser, so don’t feel too bad for him and his legacy.

Television

Another contentious one, the invention of television is generally credited to Scotsman John Logie Baird, and if we define “television” as the broadcast of moving images, he was the first to do so (privately, in 1925) – but only at a speed of 5fps. By January of 1926, he had upped the speed to 12.5fps and demonstrated it to the press and scientific community – and the rest, as they say, is history.

What, we wonder, would Logie Baird have made of HDTV, live 3D broadcasts and 4K movies showing on vast OLED screens? Without his initial breakthrough, we probably wouldn’t have any of those things today (on the flipside, neither would we have Keeping Up With The Kardashians).

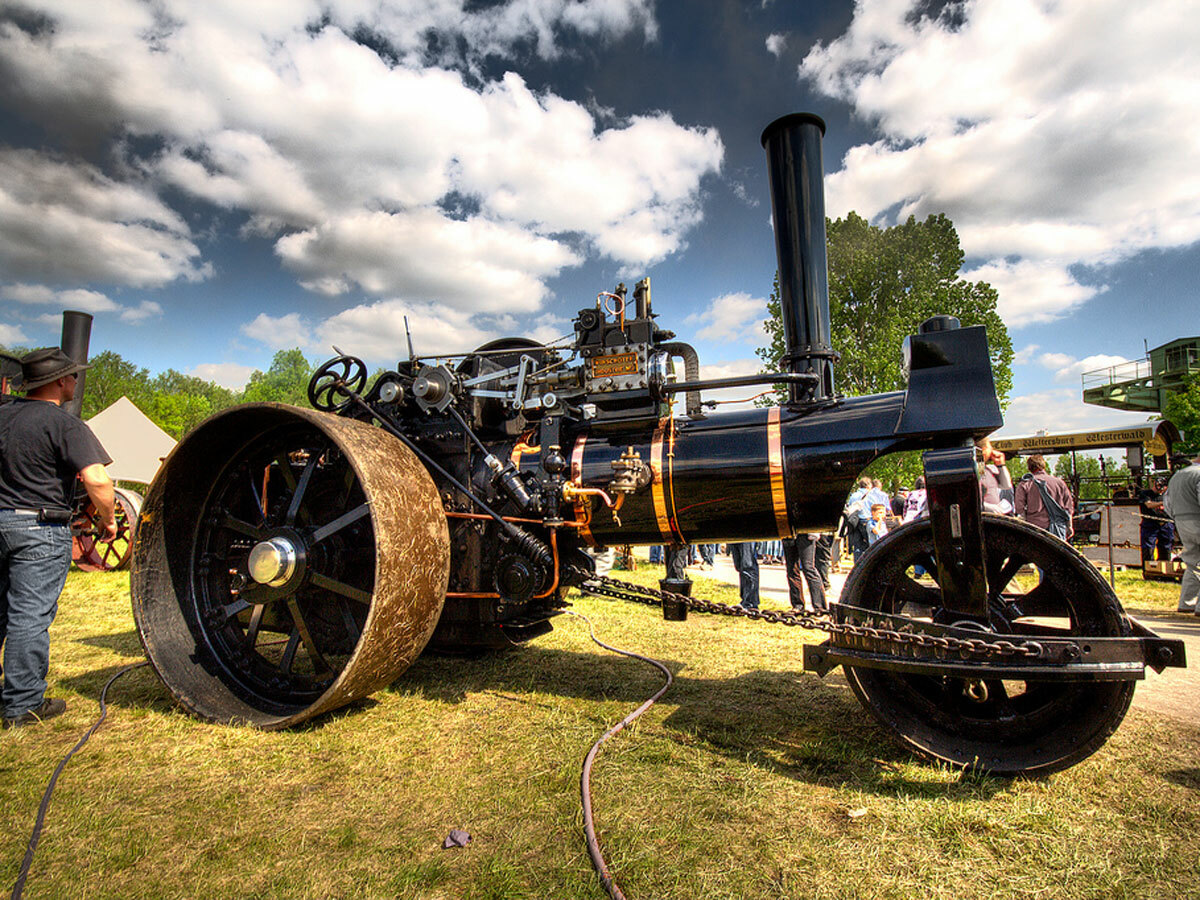

Steam engine

While the concept of a steam engine goes all the way back to ancient Greece, James Watt’s 1871 developments to the existing Newcomen engine (used to pump water out of mines) made steam power quite literally the driving force behind the Industrial Revolution, and him one of the architects of the modern world. He also came up with the concept of horsepower as a measurement of energy, and his name has been immortalised in the word we use for a unit of power: the watt.

Image credit: Thomas Mues

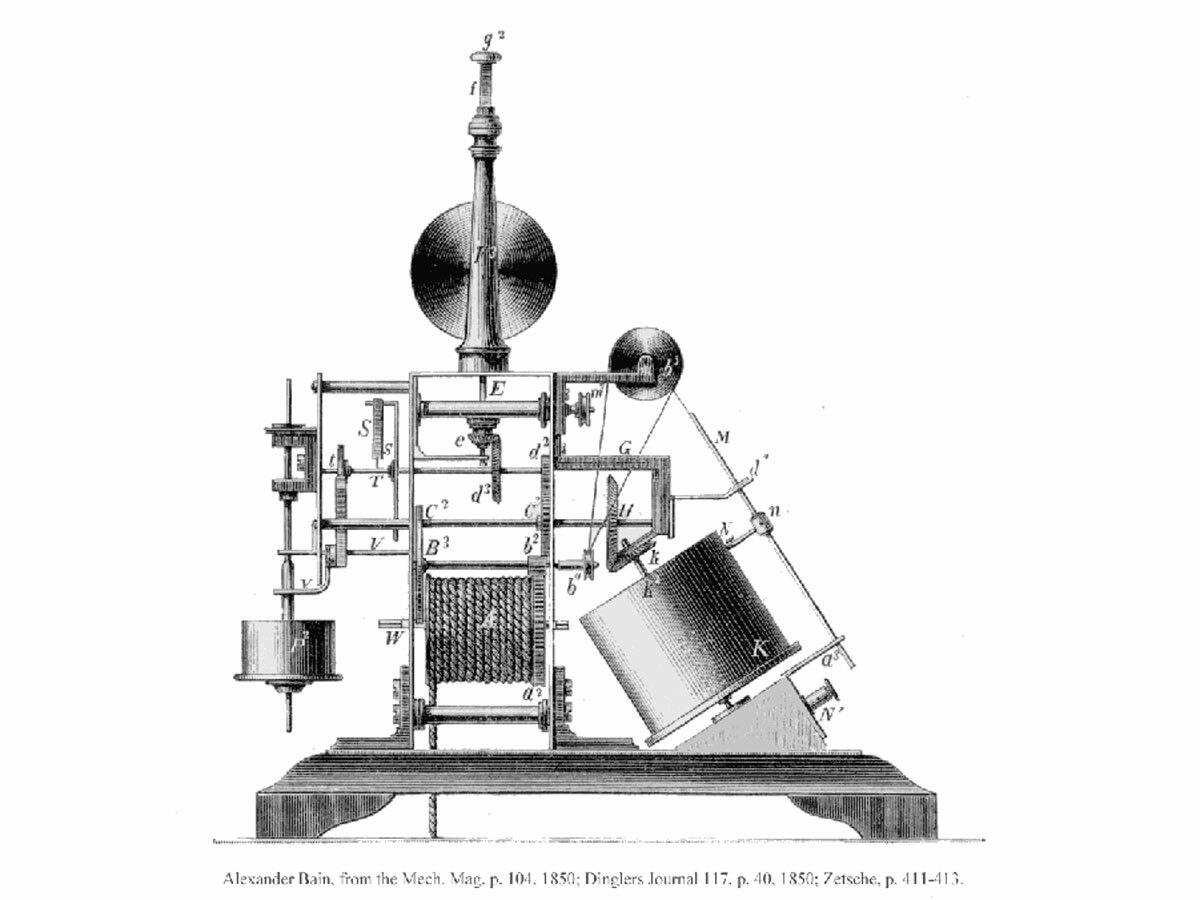

Fax machine

The first example of what would today be considered a fax machine was invented by Scots engineer and clockmaker Alexander Bain, who was awarded a patent in 1843 for a machine able to make a copy of an image via transmission. While email and MMS have overtaken fax as methods of instantly sending documents and images, Bain’s basic idea remains in use today.

World Wide Web

Without British computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee, the Internet would be a very different place. While working at CERN in 1989, Berners-Lee came up with the idea of the World Wide Web as we know it: a system that used hypertext links, domain names and Transmission Control Protocol to create a navigable “information superhighway”. If that wasn’t enough, he also designed and built the first web browser.

Oh, and if you’re interested, this is the first web page address ever: http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html.

Stereo audio

English electronics engineer Alan Blumlein was a busy bloke, being awarded no fewer than 128 patents – chiefly in the areas of sound recording, telecommunications, radar and television. But perhaps the most significant is his invention of stereophonic (or as he called it, “binaural”) sound: Blumlein realised that by recording and playing back two channels of sound through a pair of speakers, a filmmaker or musician could make audio “directional”. Stereo recordings were available soon after Blumlein came up with the concept in 1931, and by the 1970s it had firmly established itself as the standard for music recordings. Blumlein himself never lived to see that: he died in a 1942 plane crash while testing an airborne radar system. He was only 38.

Image credit: JD Hancock

Computer

Londoner Charles Babbage was a man of many talents: astronomer, mathematician, inventor, engineer and philosopher (he’s considered an influence on none other than Karl Marx). But Babbage is best known for his work in the field of mechanical computers, which he began working on as early as 1822. His “difference engine” and “analytical engine” concepts, giant programmable machines able to make mathematical calculations, were never finished in his lifetime, but their design forms the basis for later computing innovations (fun fact: a plan to construct the analytical engine is underway, and has determined that it would have the equivalent of 675 bytes of memory and a clock speed of 7Hz; the replica should be completed by 2021).

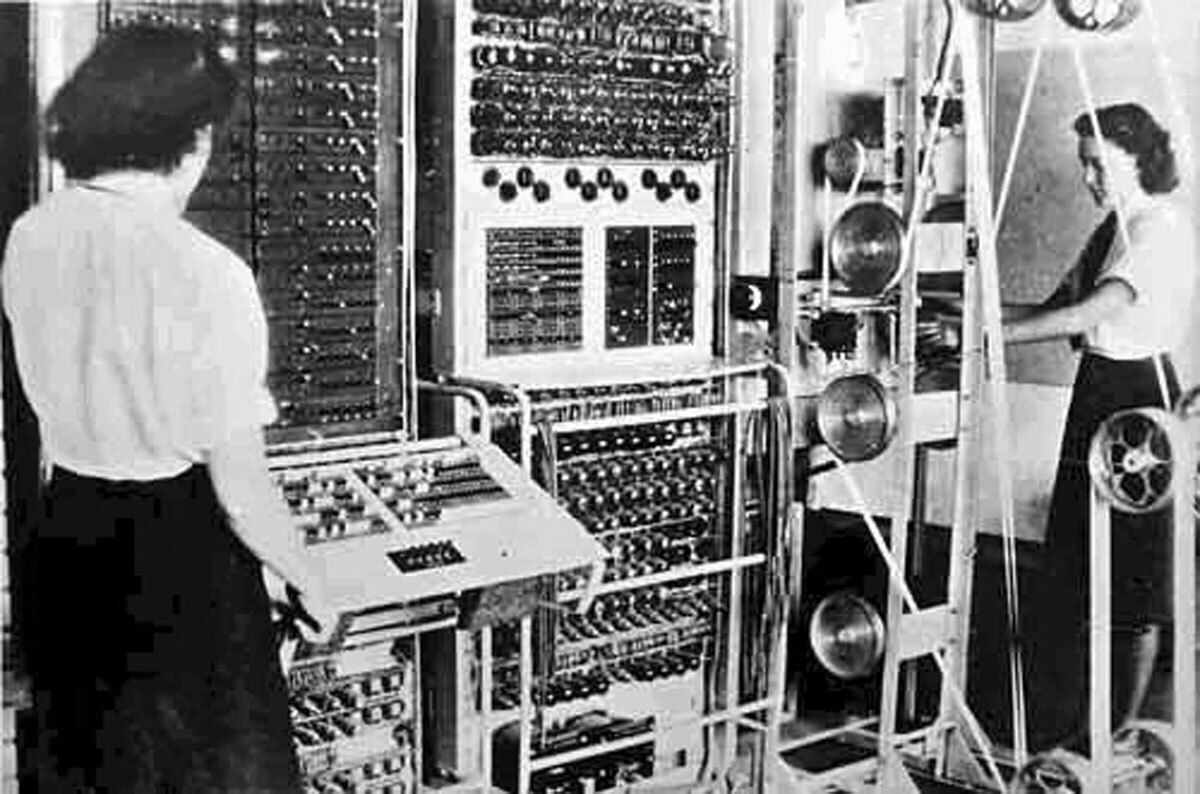

A couple of hundred years later the codebreakers at Bletchley Park built the world’s first electronic programmable computer. Colossus was designed by engineer Tommy Flowers with help from Alan Turing, and was in operation by early 1944, when it was used to decrypt Axis communications. With no memory to store programs, it had to be programmed by flicking switches and altering the wiring through plugs. Highly classified, most Colossus models were destroyed immediately following World War II and its very existence was kept secret until many years later.

Portable digital music player

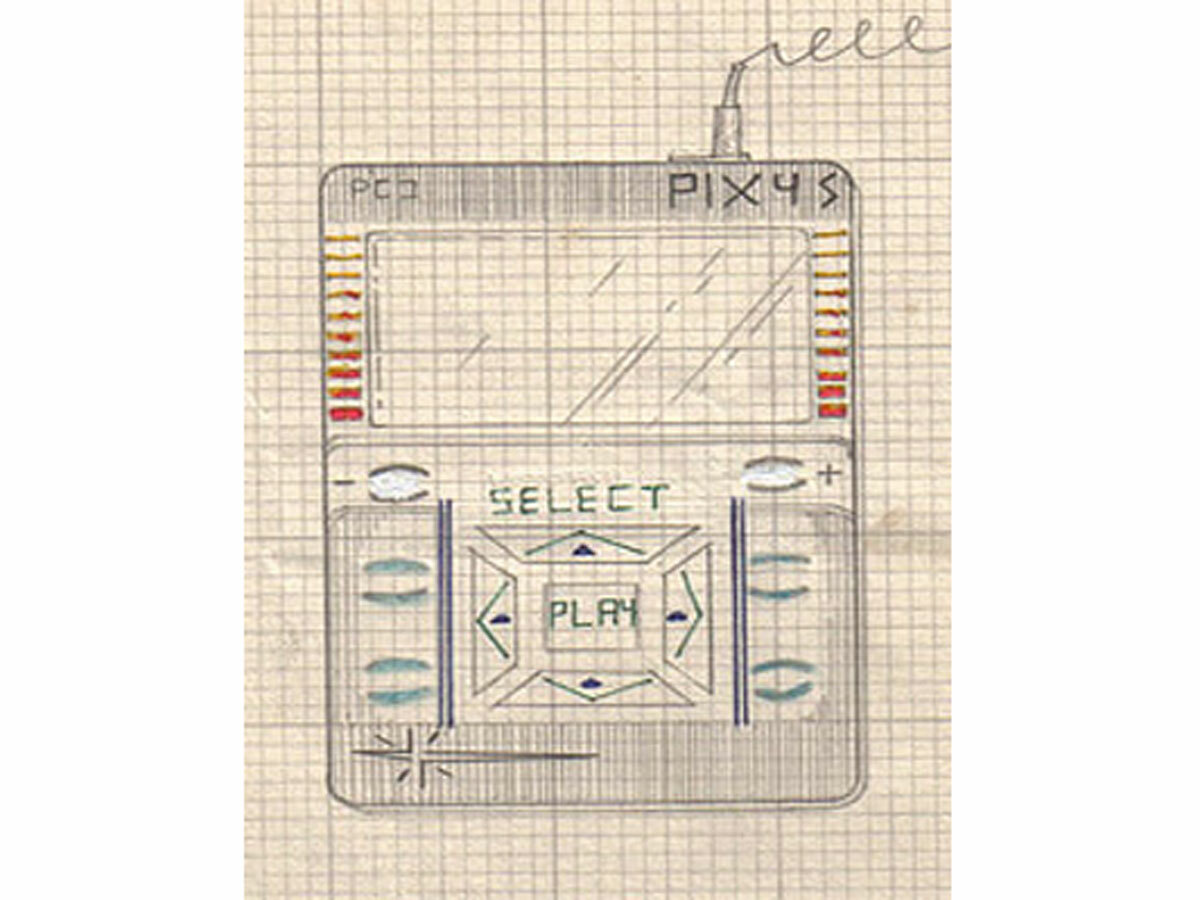

Without Kane Kramer, there’d be no iPod. In the late 1970s, the Londoner dreamt up the idea of a portable digital music player and, by 1981, he had secured a patent for IXI, a credit card-sized gizmo with a tiny LCD screen, control buttons and an all-important 8MB of solid state storage – enough for 3.5 minutes of audio.

Yes, you could only fit one (short) song on the IXI, but it was still the world’s first digital music player – a fact acknowledged by Apple in 2008 when the company was defending itself against patent infringement over the iPod. Apple called Kramer as a defence witness in its case against MP3 player-maker Burst. Kramer was cited as “the father of the iPod” by Apple, but aside from a consultancy fee he’s barely earned a penny from his invention.

Light bulb

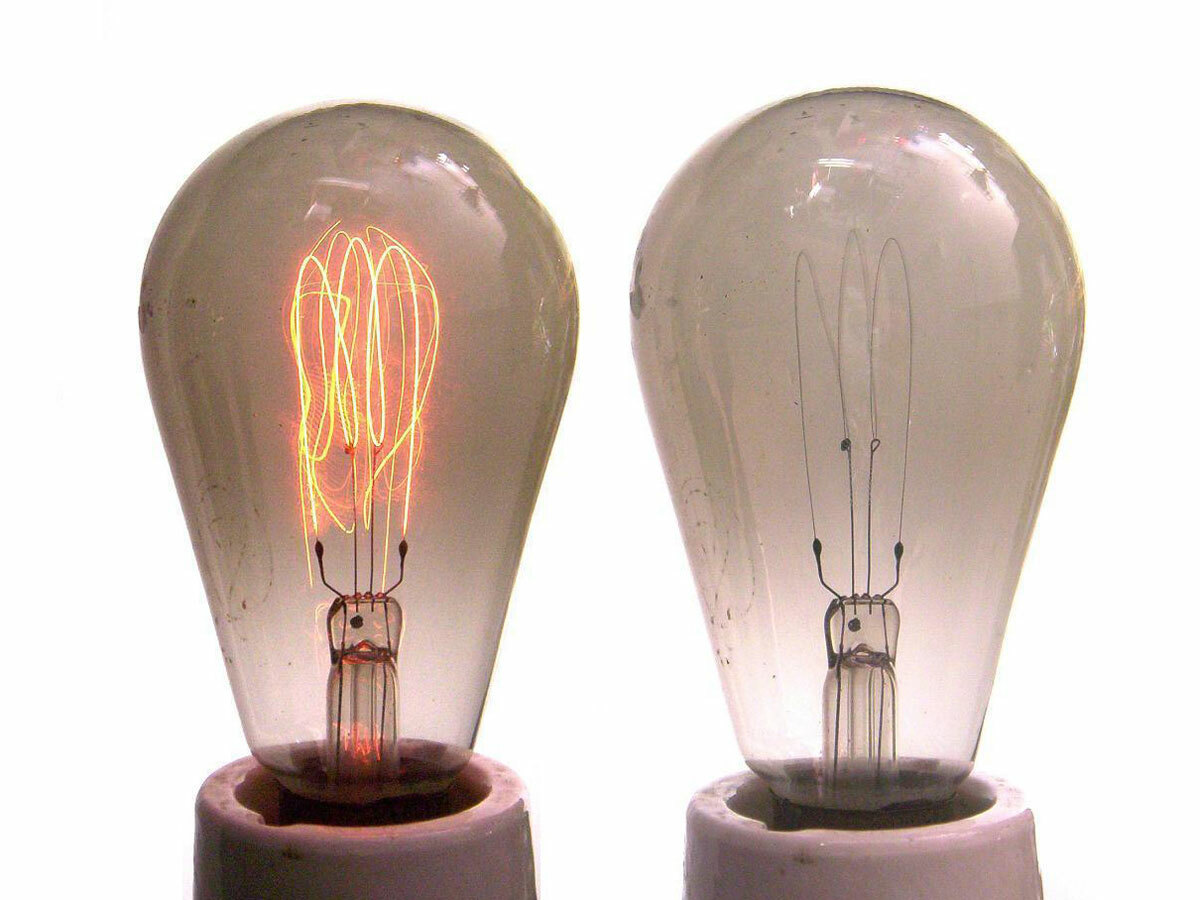

Ask most people who invented the incandescent light bulb and they’ll probably shout “Thomas Edison!” But they’d be wrong, because it’s yet another invention that can be chalked up to a son of England – namely Joseph Swan, a physicist and chemist from Sunderland.

Swan came up with the idea for an electric lamp in 1878 and was awarded a patent a couple of years later – but that didn’t stop Edison from nicking the concept, claiming it for his own and flogging light bulbs in the US. Swan, who wasn’t interested in money but rather the idea of perfecting his invention, allowed Edison to do so – probably why the latter is so closely associated with light bulbs today and Swan is a long way from a household name.

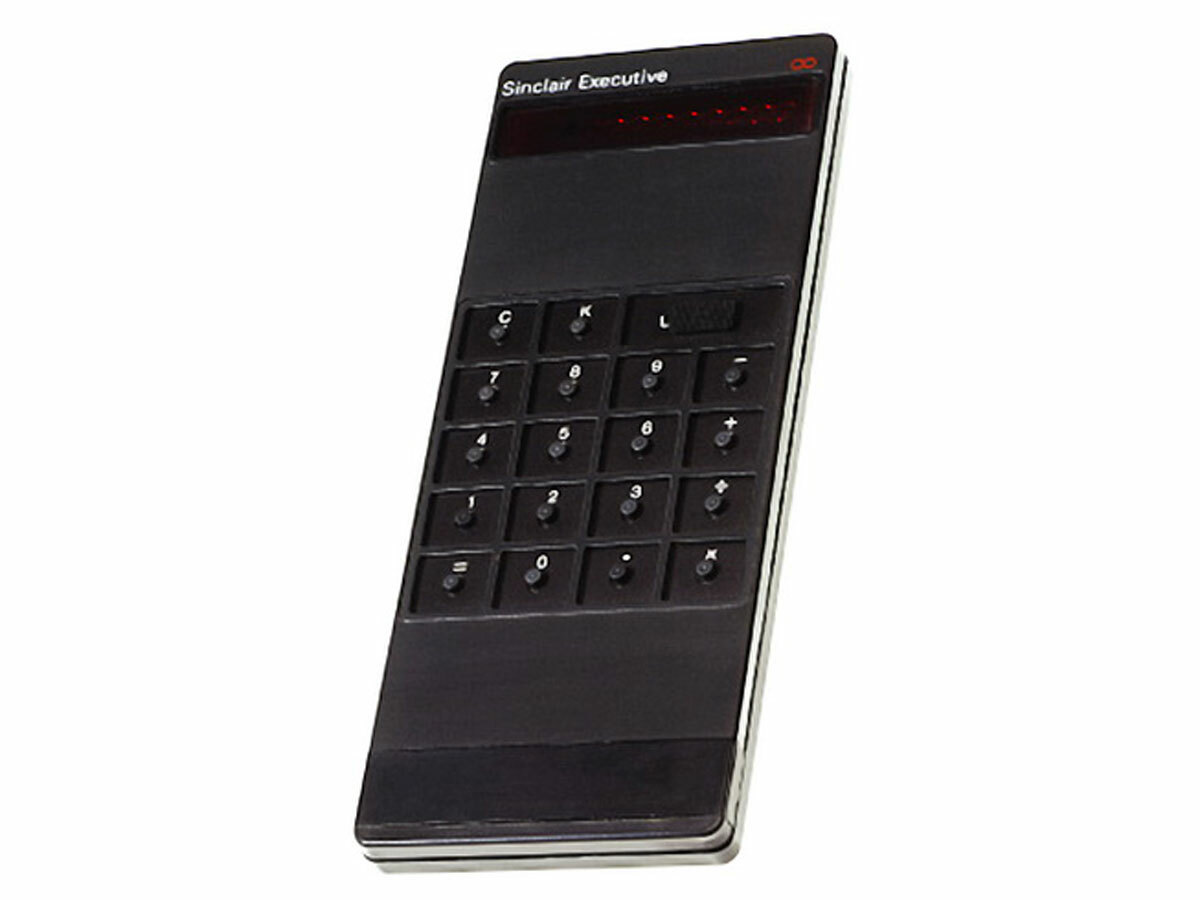

Sinclair Executive

Look at the Sinclair Executive and it’s hard to believe that it came out in 1972 – it’s about 10 years ahead of its time in both its understated design and miniature size. The first slimline calculator in the world and one of the first of a swathe of “executive toys” that filled the pockets and desktops of well-paid businessmen, the Executive was designed by Spectrum (and, er, C5) mastermind Clive Sinclair and sold at the time for £80 – the equivalent of about £700 today.

Photography

William Henry Fox Talbot is the father of photography, having invented the calotype process using paper sensitised with silver chloride all the way back in 1835 – a full four years before Louis Daguerre showed off his own method of creating an image. Talbot was the first person to make photographic images using paper and negatives – and thus informed analogue photography for the next 170-odd years.

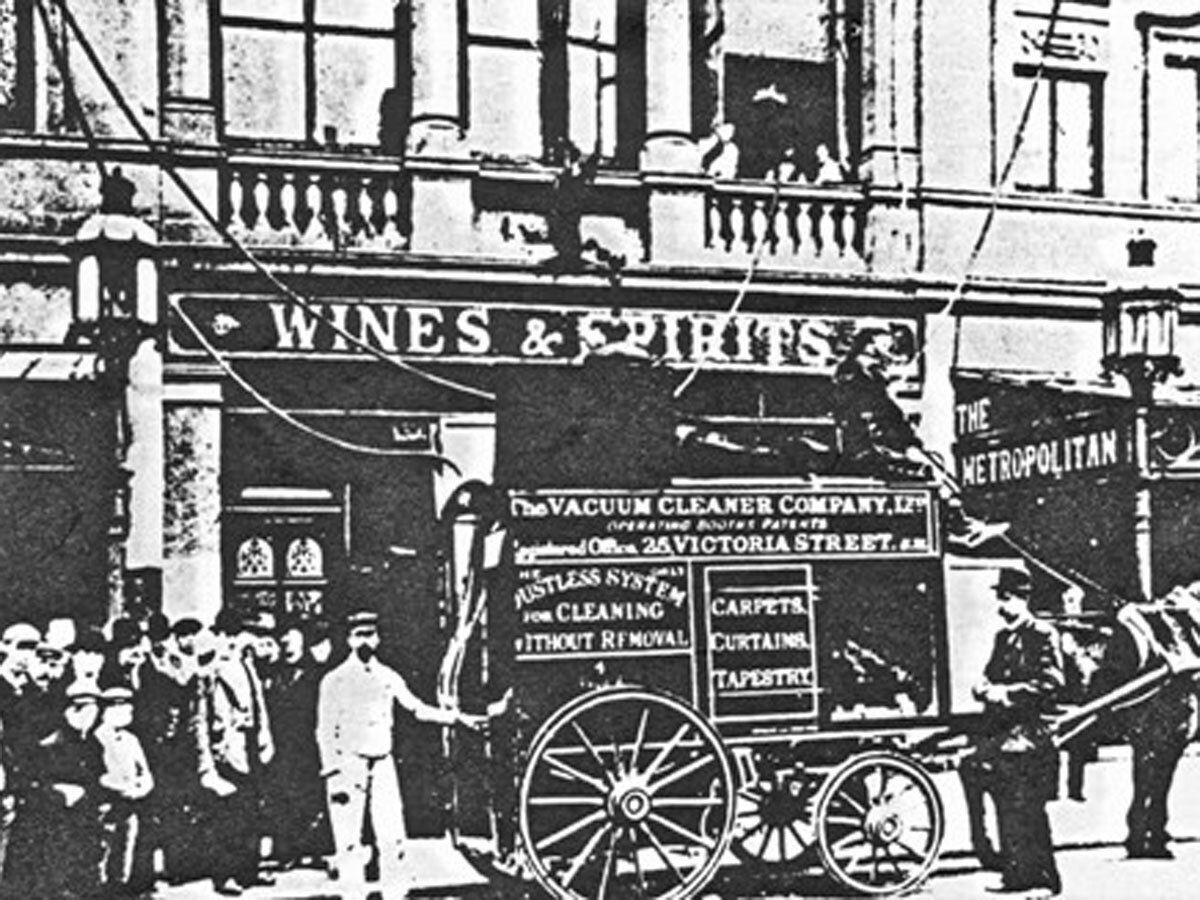

Vacuum cleaner

The powered vacuum cleaner was invented by Gloucester-born Hubert Cecil Booth in 1901. Booth had been watching a demonstration of compressed air cleaners when he had his light bulb moment: wouldn’t it be better to suck up dust into a machine than to blow it away? All modern vacuum cleaners are based on Booth’s original idea, but his own creations were better suited for large-scale industrial use than domestic cleaning and thus his American competitor Hoover overtook him to become a household name.

Hovercraft

The vacuum cleaner turned out to be pivotal in the development of our next entry, the hovercraft. Boat engineer Christopher Cockerell had surmised that if you could lift a craft entirely out of the water as it moved, it would reduce drag and mean it could travel faster. And how did he demonstrate the correctness of his theory? By building a model using a couple of tin cans and a vacuum cleaner. Cockerell took his idea to the British government and it remained a secret until 1958, when the first production hovercraft was built.

Carbon fibre

The material now famous for its use in Formula One cars and Olympic gold-winning bikes was essentially invented by engineers at Hampshire’s Royal Aircraft Establishment, who in 1963 developed a process to make the high-strength flavour we use today.

Wind-up radio

Trevor Baylis is one of Britain’s best-known living inventors, and among all his creations one stands out: the wind-up clockwork radio. After watching a TV programme about the spread of Aids in Africa, Baylis hit on the idea of a radio that wouldn’t require electricity or even batteries, thus giving people in even the poorest and most remote places in the world the opportunity to receive information about Aids and advice about contraception.

The radio has sold millions but, unfortunately for Baylis, the company he worked with to produce the radio eventually swapped clockwork for rechargeable batteries. This meant his patents became outdated, he stopped receiving royalties and he’s now living in poverty.

Image credit: Ewan Bellamy

Self-winding watch

Bolton man John Harwood became the saviour of lazy timepiece wearers when, in 1923, he developed the self-winding wristwatch.

Harwood’s system employed a pivoting weight that swung as the wearer moved, winding the mainspring as it did so. Not only did this mean it didn’t have to be manually wound, it also meant the body of the watch could be completely sealed to prevent water or dust getting in. Bonus!

Jet engine

While the first operational jet engine can be credited to German Hans von Ohain in 1937, several years later the concept was patented by a Brit – and an RAF man at that. Frank Whittle patented the idea of a turbine-driven jet engine in 1930 but couldn’t find anyone to stump up the thousands of pounds required to build one until years later. In the end, the first Whittle-designed turbojet engine wasn’t built until 1937, by which time von Ohain was already building the first flyable jet-powered plane.

Image credit: Lee Cannon

Maglev train

Another RAF officer, another breakthrough in transport engineering. Eric Braithwaite was among the team that developed autopilot technology during the Second World War, but he’s far better known for what he did afterwards: build the first working maglev train prototype and thus revolutionise train travel. Maglev trains use electromagnets to “levitate” their carriages from the track and propel them along. Because of the lack of physical contact between train and track, maglev trains are cheaper and easier to maintain than wheeled trains – but more expensive to build.

Image credit: Lars Plougmann

Cat’s eye

Yorkshireman Percy Shaw came up with the idea of the cat’s eye during a nighttime drive through a suburb of his native Halifax. Shaw was using the reflective surfaces of disused tramlines on the road as guides and realised that it would be pretty straightforward to install small reflective spheres in the asphalt. And his invention went further, with the spheres being automatically cleaned as cars drove over them and pushed them into the ground.

He was awarded a patent for the cat’s eye in 1934, thus boosting road safety in Britain and across the world.