Up close and personal with Crossrail’s monster tunnelling machines

With Europe’s largest megaproject taking shape deep beneath London’s streets, Stuff descends into the bowels of the earth to find out more

Seven floors below the surface of London, a five-minute climb down aluminium steps that lead into the huge, concrete-lined chambers that will make up Farringdon Crossrail station, this mighty project doesn’t look like a Digital Railway. It looks like an enormous hole in the ground.

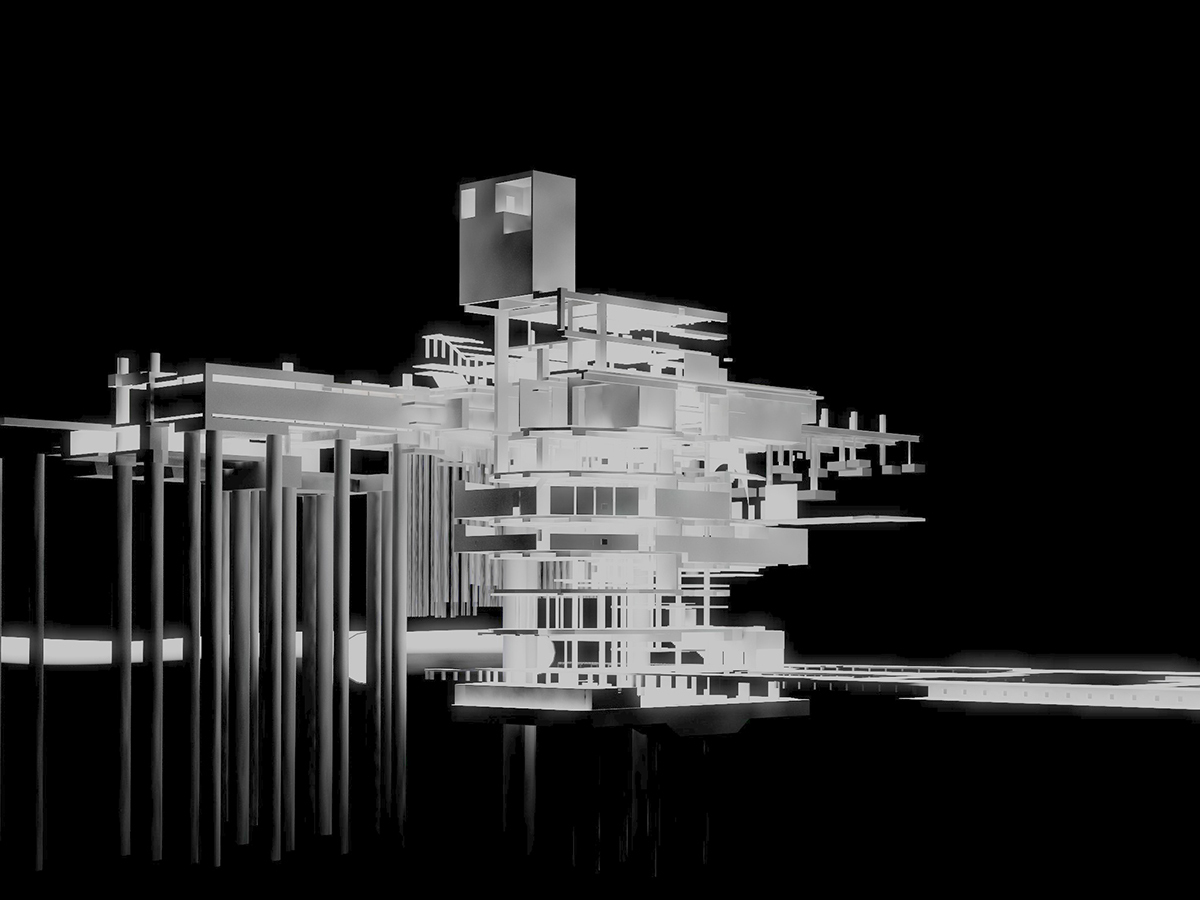

Which, of course, it is, but Crossrail isn’t just a physical system. In and around these immense tunnels – the platforms are so big that some station entrances will be more than a quarter of a mile apart – an invisible structure is evolving. All around us there are stations, platforms, pilings and escalators, built as digital models, visible in augmented reality, waiting to be realised in concrete and steel. Looking through the augmented reality app built specially for the project, you can see the huge components that will be clicked into place.

This isn’t just a fun app for checking out what will be here in 2018, though. In fact, the app is unlikely to make it into public use – as the site manager explains, publishing the layout of every cable and substructure of London’s new transport mainline would be a spectacularly unpopular move with the police and security services. But for the people building Crossrail, and for the people who will run it for the next century – these things are built with a minimum 120-year lifespan in mind – the physical railway and the digital railway are inseparable.

Without a computerised reflection of what’s being built, Europe’s largest engineering project would be impossible to co-ordinate; there are 10,000 people currently working on Crossrail’s 40 construction sites. And as the real-life tunnels and walls and supports go into place, the digital model grows and adjusts: engineers watch the components move into place through the AR app, which registers when they meet with the digital model and updates it. Measuring lasers, movement sensors and even iBeacons keep a digital eye on the real-world environment and adapt the model, not just for the engineers working on Crossrail now but also for their successors, decades from now, who will have an ever-changing digital copy to refer to.

This article first appeared in the April 2015 issue of Stuff, the world’s best-selling gadget magazine. We’ll print loads more fascinating features, news and reviews and bring them right to your house, if you subscribe here.

Digstarter

Work on Crossrail has been informed by London’s last engineering megaproject, the Olympics – another multi-billion build in which large numbers of different contractors worked across many different sites. The construction industry is fiercely competitive and contractors are traditionally reluctant to exchange ideas, but Crossrail has pioneered a crowdsourcing project model. Ideas from any contractor are suggested, funded from a common pot of seed money and trialled on small areas of the project.

If they work, they’re then developed into more widespread use. These can be simple things like printing safety advice on workers’ gloves, or more technical innovations like lightweight aggregates. One particularly bright idea is to create tunnels that take the excess heat from the trains (and passengers) and turn it into electricity to feed back into the grid.

Crossrail by numbers

- 200 million: Passengers (per year)

- 26 miles: Length of new tunnel dug

- 4.5 million: Tonnes of earth moved

- 62 million: Hours worked so far

More reading › The bleeding edge technology shaking up the Olympics

Tunnel vision

At this stage, though, for all its digital wizardry and forward-thinking crowdsourced ideas, Crossrail is still very much a dig. The ‘fit-out’ stage is yet to happen; there are no rails, cables or drainage in the new Farringdon station as we walk down the enormous tube that links the east and west platforms. The walls in the deeper tunnels still show a stubble of the stiff steel wires that are mixed into spray-on concrete to give it strength.

This fibre-reinforced concrete (or ‘shotcrete’, as it’s known to anyone with a rolled-up copy of the Screwfix catalogue in their back pocket) is hosed onto the walls at high velocity in several coats, reaching a thickness of half a metre on average. On a regular building site, the damp concrete is vibrated using power tools; in the Crossrail tunnel, a metal structure the size of a road bridge is pressed against the domed ceiling and thrummed with ultrasonic ‘limpet’ vibrators. Once dry, it’s tested for strength using a bolt-firing gun that they’re only too happy to demonstrate, but which journalists are sadly not allowed to have a go on.

How much?

- £37 billion: Eurofighter programme (UK contribution)

- £34 billion: 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics

- £15 billion: Crossrail

- £10 billion: 2014 Brazil World Cup

- £6.2 billion: Large Hadron Collider

Now that’s what I call boring

Heading deeper still, we reach the end of the tunnel, where a digger is tearing out sofa-sized scoops of sub-London gubbins: the behemoth tunnel boring machine has finished its work here, but the end of each tunnel is domed for extra strength. The digger’s work doesn’t exactly look subtle, but above the face of smashed rock and scooped clay, an engineer’s spot laser tracks the concrete dome that’s forming, matching it up to the digital model that lives on Crossrail’s servers.

At this stage, though, it’s still the TBMs that get all the headlines, and rightly so. Like mechanoid versions of the giant sand-worms in Frank Herbert’s Dune, these 980-tonne beasts chew through the earth using a cutting head seven metres across, laying preformed concrete tunnel sections behind them as they crawl along their routes. The ground beneath London is already a tangled mass of tubes, sewers and holes and the TBMs have to thread carefully through it, sometimes missing a Royal Mail underground line or even a Tube station by as little as a foot.

There isn’t even a fixed definition of what constitutes surface level in London – Farringdon, for example, was ‘built on stilts’ by the Victorians to avoid flooding, so the real ground level is a couple of basements below Clerkenwell Road. Speaking as someone who’s had trouble parking a Nissan Micra in broad daylight, the idea of performing such delicate manoeuvres in a 150m-long, 1000-tonne vehicle, seven floors down, sounds tricky. I think I’ll wait for the train.

The world’s biggest power tool

- The TBM’s ‘thrust force’ is 58,000 kiloNewtons, which is over 3000 times the bite force of an adult great white shark.

- A ring of 10 hydraulic rams steer the GPS-guided TBM to within millimetres of its target, moving at around 100 metres a week (0.0004mph).

- As the TBM drills through the earth it pushes out rings of 1.6m-wide concrete segments, leaving freshly laid tunnel in its wake.