PlayStation at 20: How the PlayStation changed gaming

As the original PlayStation turns 20, we look back at its era-defining impact on the world

In the early ’90s gaming was for kids. Games were a hobby you grew out of. Something to be banished to the attic with Action Mans and Care Bears in your teens. But then the PlayStation arrived and things would never be the same again.

Sony’s first console, which turns 20 today, was nothing short of game changing. The PlayStation had it all – revolutionary hardware, smart marketing and groundbreaking games.

By the time it was discontinued in 2006 more than 100 million PlayStations had been made and Sony ruled the games business.

An inauspicious start

Not that anyone was sure Sony’s gamble on games would pay off back in 1994. Sony was an upstart and many, including some within the business, wondered if the company knew what it was doing.

There were good reasons to be doubtful.

Sony’s contribution to games pre-PlayStation had largely consisted of publishing consistently terrible games based on action movies such as Cliffhanger. What’s more, Sony never intended to make a console.

The path to PlayStation began in 1989, when Nintendo asked Sony to help it make a CD-ROM version of its Super NES console. All went well until Nintendo got all paranoid about Sony using the deal as a stepping stone to getting into the console business. So the day after the Super NES CD project was revealed in 1991, Nintendo announced it was dumping Sony for Philips.

Furious at the humiliation, Sony decided to get revenge by, er, making its own console.

Sound and vision

From the off the PlayStation had technology on its side. The console was a beast, offering state-of-the-art 3D graphics and CD storage. For a gaming generation raised on a 2D diet of Sensible Soccer, Mario and Sonic, the PlayStation’s visuals were jaw-dropping – a feature rammed home by Sony’s T. Rex demo, a demo so good it doesn’t look too shabby even now.

The eye candy was backed up with top-notch audio thanks to the CD drive, which let game makers use recorded music instead of computer- generated chip tunes.

And while Sony made a monster bit of kit, its main rivals dropped the ball.

Sega designed its Saturn console as a 2D powerhouse before hurriedly tacking on 3D capabilities after getting the jitters about what Sony was promising. The result was a complex console that even Sega’s own developers admitted that only the very best game makers would be able to use well.

Nintendo, meanwhile, went 3D but refused to join the CD age. Instead it stuck with game cartridges, a move that limited the Nintendo 64’s sonics and left N64 owners paying around £20 more per game than their PlayStation-owning pals.

The PlayStation’s 3D and CD advantages were enough to persuade Final Fantasy creators Square to join Team Sony after years of loyalty to Nintendo. And, armed with Sony’s tech, Square made Final Fantasy VII – the first Japanese role-playing game to make it big in the west.

In control

Ergonomically terrific, Sony’s hardware innovation didn’t end with what was in the PlayStation either, for it also reinvented the game controller.

Prior to the PlayStation, ergonomic game controllers were like unicorns. Game pads meant flat plastic slabs that threatened to turn your mitts into rigid claws if you played too long. Or – if you were unlucky enough to find an Atari Jaguar under the Christmas tree – a telephone keypad that also turned your hands into claws but did it with extra ugliness.

The PlayStation controller was different: it was a three-dimensional object designed with human hands in mind. Goodbye cramp, hello extra playtime.

Things got even better in 1997 when Sony launched the DualShock, a new version with twin analogue sticks and vibration. Nintendo’s response? A three-pronged plastic fork that seemed tailor-made for octopii. Tellingly, it’s the PlayStation controllers that became the blueprint for most of the gamepads that followed.

Games galore

So the PlayStation had the hardware – but that wouldn’t have mattered a jot without great games. Fortunately, PlayStation owners had plenty of stellar titles to choose from, including first-rate ports of arcade hits Ridge Racer and Tekken, the motor fetishism of Gran Turismo and the Mario-challenging Crash Bandicoot.

The PlayStation’s games established many of the genres we now take for granted but were rare sights before that little gray box arrived. Tenchu: Stealth Assassins and Metal Gear Solid brought stealth to the fore. The totally bonkers hip-hop adventures of PaRappa the Rapper established music games while Cool Boarders and Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater switched gamers on to the thrills of extreme sports.

The PlayStation was also where horror games finally got their claws into us, starting with Resident Evil, which backed up its b-movie frights with shockingly hammy dialogue (not least the ‘I hope this is not Chris’ blood line’), and followed by the twisted Silent Hill. Games that would be hard to imagine making waves in the family friendly world of Nintendo.

Rebranding gaming

And then there was WipEout, the hi-octane future racer soundtracked by The Chemical Brothers and Orbital that – here in Blighty at least – plugged the PlayStation into the club scene.

The promotional campaign saw WipEout being put into superclubs such as Cream in Liverpool and Bristol’s Lakota, together with controversy-seekings ad from its publisher, Sony subsidiary Psygnosis.

“Psygnosis was left to get on with its own stuff so it was doing things that Sony, in a million years, wouldn’t have done directly,” says Glen O’Connell, the former head of PR at Psygnosis. “Stuff like the WipEout ad with Sara Cox with a nosebleed. Nice, clean-living Sara Cox from Radio 1 looking like some sort of heroin overdose.”

Courting controversy

Although early PlayStation ads like the Society Against PlayStation played it safe, over time Sony’s marketing became more daring and distinctive with efforts such as the Double Life adverts.

Several campaigns got into hot water. In 1995 Sony went to the Glastonbury Festival and handed out perforated postcards with the PlayStation logo. Officially the cards were for disposing of chewing gum, but they also happened to make ideal roaches for cannabis joints. Sony also courted controversy with an advert for Cool Boarders 2 that talked about needing powder and “having to get higher than last time”.

When complaints flared up, Sony said it was snowboarder slang. Any drugs references were purely coincidental. Honest.

The push to connect PlayStation with youth culture worked. “The PlayStation looked like any console but had content on it that people in their twenties were doing in their everyday lives. It talked to people about the interests they had, whether that be club culture, sports, whatever,” says O’Connell. “At that time the DJs were playing music by some of these bands that also happened to be in these games and I think that touched a nerve with a lot of people.”

The first PSX superstar

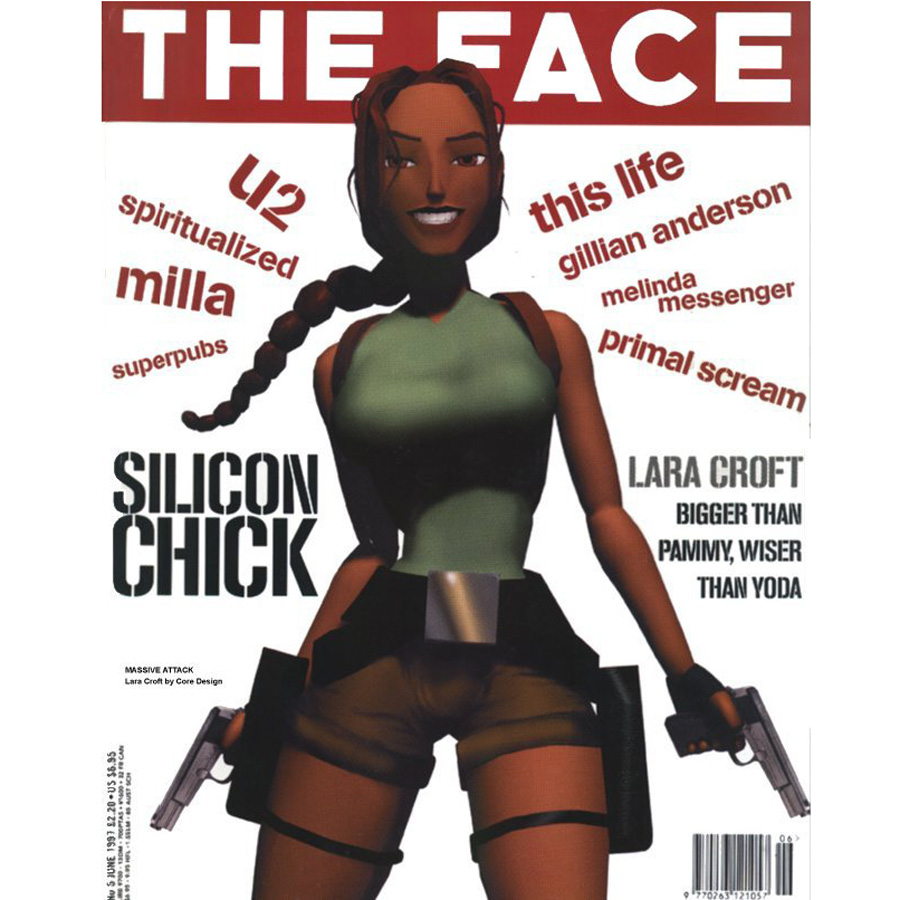

Tomb Raider gave Sony’s quest to position its console as an entertainment system rather than a toy a further boost. Although the Saturn got it first, Tomb Raider became synonymous with PlayStation and Lara Croft became a star.

For a while Lara was everywhere: on the cover of style bible The Face, in video footage at U2 concerts and peddling Lucozade. And, despite her unlikely proportions, the idea of the female gaming hero was startling enough for Lara to be hailed as a symbol of girl power.

By the time the PlayStation 2 arrived in 2000, gaming had been transformed. PlayStation had taken games mainstream, established new genres, improved controllers and ensured consoles were no longer just for kids.

It set the template for gaming as we know and 20 years on we’re still living in the gaming world the original PlayStation created.

READ MORE: PlayStation at 20 – the 25 best PlayStation games ever