Schoolkids ‘hacking’ iPads should be celebrated, not punished

"We don’t need no iPaducation," is the depressing cry from LA – but educators shouldn't freak out about kids daring to explore technology, says Craig Grannell

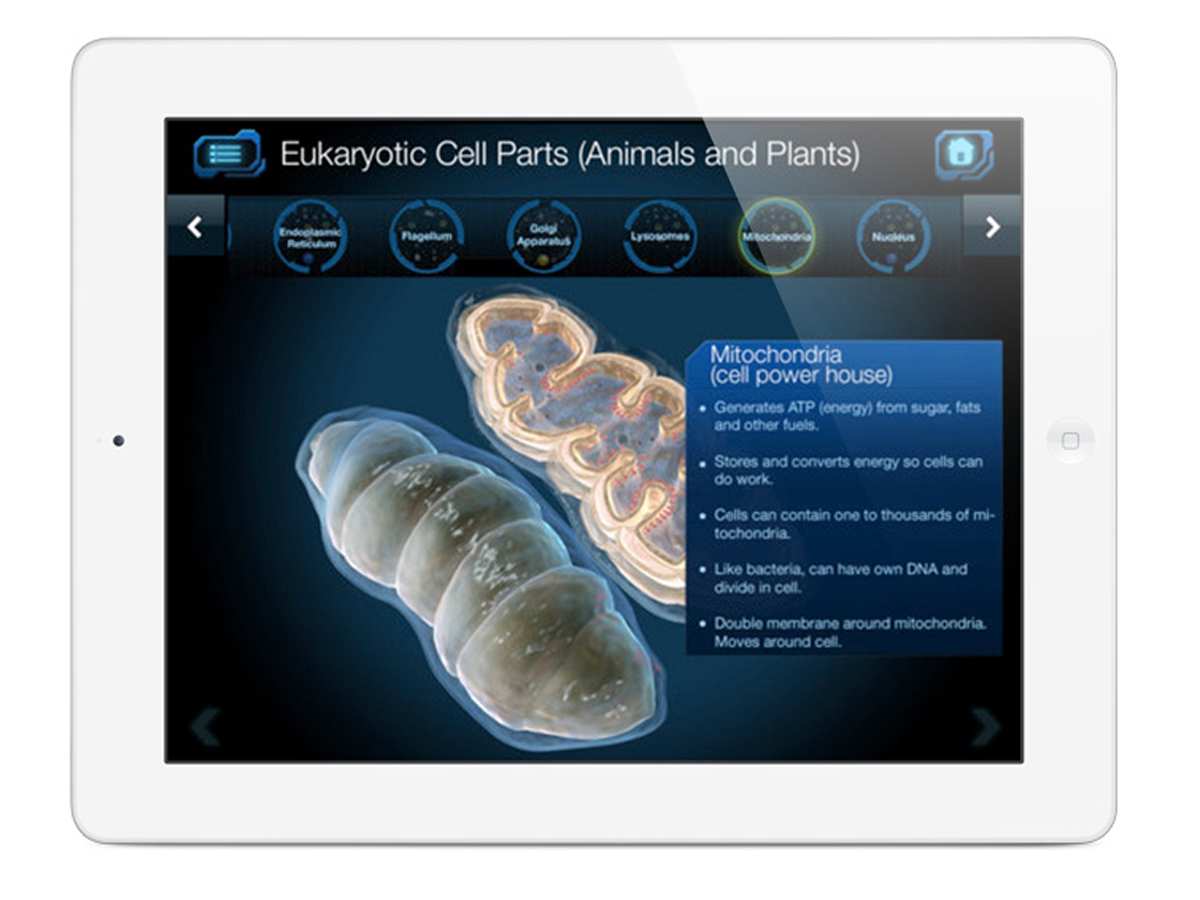

Headlines have flared up recently about the ‘controversy’ surrounding a high-profile iPad rollout at Los Angeles schools.

Students have come under fire for ‘hacking’ iPads and using them for ‘unapproved’ purposes. Critics have slammed the schools for providing students with iPads that they could subsequently – horrors! – surf the internet on. Because presumably that would lead to the end of society as we know it.

These events make me imagine plenty of old duffers are bouncing around the education system, harrumphing and arguing everyone would be better off with a jolly good book. Never mind that many of the books in schools are full of outdated information, have missing pages, and boast surprisingly numerous pictures of male members drawn in biro; but books were good enough for them, damn it, so they should be good enough for these modern kids with their ‘technology’ and their ‘facebooks’ and their ‘twerking’.

Image credit: Lotte Ch

Technology frightened teachers…

What all this demonstrates is that while gadgets and technology increasingly play a major role in society, their place in education remains all too fragile. I remember things being little different during my own school days, which coincided with the beginning of the home-computer revolution.

Back then, Sir Clive Sinclair was trying to convince people to hand over 80 quid for a plastic computer kit you had to assemble and solder yourself. On the other side of the Atlantic, the Apple II had cemented itself in the public consciousness, albeit largely as a hobbyist pursuit. It was an exciting time, full of potential — especially if you were a kid with an instinctive love of technology.

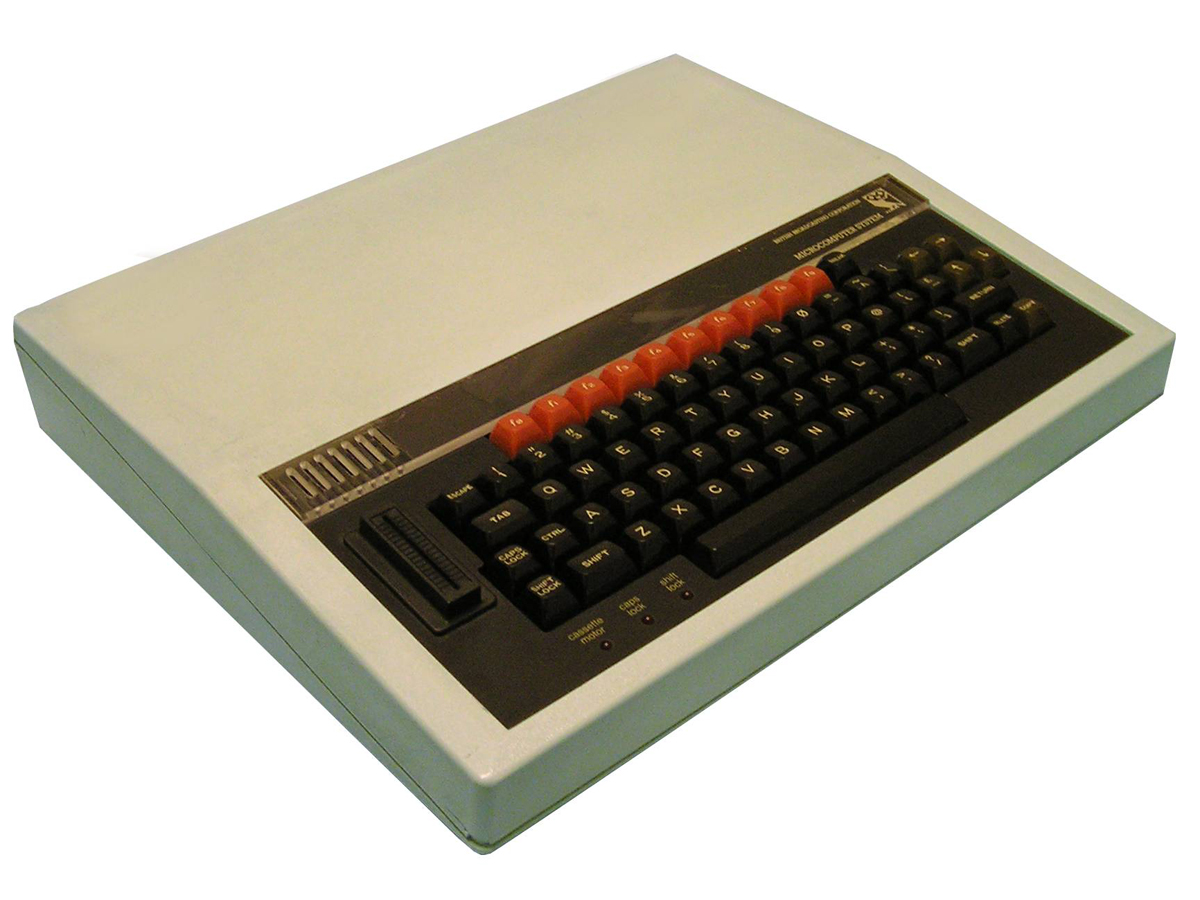

Yet at my primary school, a solitary Commodore PET lurked unloved and undusted in one of the tiny reading areas situated at the back of each classroom. A year or two later, wheeled desks mysteriously appeared with BBC Micros begging to be experimented with. But the teachers seemed almost fearful of technology; and despite this being a state school, they thought our futures would be better catered for if we all regularly sat around a piano and sang about Jesus.

Image credit: Philip Howard

…And little has changed

By the time secondary school beckoned, anything related to carols was rightly banished from everyday school life and confined to religious studies, but still technology barely made a dent in our lives. Occasionally, a maths lesson would involve sitting in front of an Acorn Archimedes while a teacher looked disapprovingly at a set of instructions, twisting and gurning their face as if attempting to decipher some long-lost arcane language. Even during graphics A-levels, a small suite of Macs received only scant attention, despite being infinitely more powerful than the archaic drawing boards we mostly sat at.

It’s sad to see how little has changed. We’re in the midst of another technological revolution, where sooner or later almost everyone will own their own mobile device. Children today need to be armed with the knowledge that will enable them to thrive tomorrow. Regarding what happened in Los Angeles, the ‘hacking’ element was probably overblown — educator and head of IT at the world’s first 1:1 iPad school Fraser Speirs theorised the schoolchildren most likely merely removed personal profiles from the devices so they weren’t locked out of Safari.

The kids are alright

But had the hacking been real, that would have been something to truly celebrate. If kids take an interest in technology and want to bend it to their will — especially relatively closed platforms like iOS — this should be encouraged, because it shows initiative. It’s interesting to compare what happened in Los Angeles to a One Laptop Per Child experiment that occurred a year ago.

Motorola Xooms were dropped off at Ethiopian villages, with no instructions. The idea was to see if children could teach themselves to read, using preloaded apps. Within minutes, one child had opened a box and powered the machine up. Within weeks, groups of children were singing in English, led by ABC apps. Within months, they’d hacked Android, reenabling the disabled camera and customising their devices. It would therefore be depressing to think that kids in the west could have their devices confiscated for merely browsing the web, all because of arbitrary restrictions imposed by old-fashioned educators who wrongly think they ‘know best’.