Time Waits For No One: how tech changed music forever

We take a look back at music formats from the dawn of recorded sound to the latest streaming tech, and everything in between

A liquid takes the exact form of its container. The milk in a milk bottle is exactly milk bottle shaped until the moment you slosh it onto your Rice Krispies – and the same is true of pop music.

In the 100 years or so that we’ve been recording sound there have been a number of delivery systems used to sell recorded music to the public. Each one has left its mark on the music of its era.

I can’t think of one pop act that’s lasted a whole century – but The Rolling Stones have endured for fully 50% of the sound recording era. If we can find any barometer of the way that technology has shaped pop music, that leathery-faced troupe of bluesmen from the Home Counties are our best bet.

The Wax Cylinder

Heyday: 1890 − 1910

Technical description: Super-inventor Thomas Edison came up with the idea of recording the air-pressure waves that constitute sound onto a revolving cylinder in 1877. The principle is simple enough. Air pressure waves vibrate a diaphragm in much the same way as they act on the eardrum, the vibrations are passed on to a needle that traces the shape of those oscillations onto a revolving cylinder. Initially impressing the grooves on tin-foil Edison later moved on to hard carnauba wax. The cylinders would wear out after a few hundred plays. Today’s music moguls can only dream of such perfect built-in obsolescence. Have a listen here.

Cultural impact: Incalculable. Even though early gramophones were an expensive luxury, and the cylinders couldn’t be mass-produced in significant numbers, the fact that a live musical performance could be recorded changed everything. Composer John Philip Sousa, who for non-sousaphone players is best remembered as the composer of the Monty Python theme, memorably described wax cylinders, which were sold in small tins, as ‘canned music.’

Key Stones Recording: They’re not that old! It’s a near-certainty that vintage Jazz fan Charlie Watts has a few recordings of the period in his record collection though. Here’s Charlie’s Jazz band in full flight. The music’s a little late for the cylinder era, but just listen to the man play.

The 78rpm Shellac disc

Heyday: 1930 − 1960

Technical description: A flat-round black disc that all but the most aggressively modern music fans will recognise as a record, the 78 followed the same basic mechanics as its predecessor (and sometime contemporary) the cylinder. From the 1920s ‘electrical’ recordings used microphones and and electrically driven cutting lathe, but the principle remained the same. 78s were easier to store than their tubular cousins and — eventually — sounded better too. They tended to be cheaper than cylinders and two-sided discs were perceived as being better value.

Cultural impact: The 78 laughed in the face of the two minute time limitation that constrained early wax cylinders. Ten inch 78rpm singles had 50% more play time — a full three minutes of sound. It’s the legacy of the 78 that, to this day, pop songs tend to be about 3 minutes in length. Longer pieces were collected into ‘albums’ of multiple discs. As the discs were two-sided, the 78s introduced the idea of a ‘B-Side.’The shellac discs were also much more fragile than their vinyl successors. Which is why until surprisingly recently recording artists’ royalties always had a sum deducted to allow for ‘breakages.’

Key Stones Recording: The Stones’ own records started appearing after the demise of the 78, but it’s almost a certainty that Mick and Keith would have learned their blues licks playing along to 78s at home. Certainly Charlie remembers owning 78rpm records by Jelly Roll Morton, and Charlie Parker. The last major 78rpm release was Chuck Berry’s ‘Let It Rock’ / ‘Too Pooped To Pop’ on the Chess label. And, as we’re about to discover, Chuck was a big influence of the Stones.

The 45rpm single

Heyday: 1960 − 1990

Technical description: Smaller and hardier than the shellac discs that came before, the 45 could endure the rigours of autochanger devices that slapped one disc down onto the previous one to offer (almost) continuous music. The format was developed by RCA as an answer to Columbia’s 33rpm long-player format. Of which more in a bit. The 45 was a tough little beast. Made for jukeboxes and parties and improbable dances on beaches. The 45 arrived at around the same time that the NME printed their inaugural Hit Parade and 7” singles and the Top 40 were a marriage made in pop heaven.

Cultural impact: The three minute paradigm imposed by 78s endured for at least a decade. Musicians were encouraged to stretch out by Bob Dylan’s 6 minute ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ in 1965, but radio formats were by then so dominated by the three minute song that record companies did their best to discourage their artists from following Dylan’s lead. The format of a 45rpm pop single has become so ingrained in our culture that it’s hard to write a song that doesn’t fit the template. You’ll still see the odd ‘boutique’ 45 release but the day the music died, at least from the 45s point of view, was in 1993 when Culture Beat’s ‘Mr Vain’ hit the Number One spot without a 7” release.

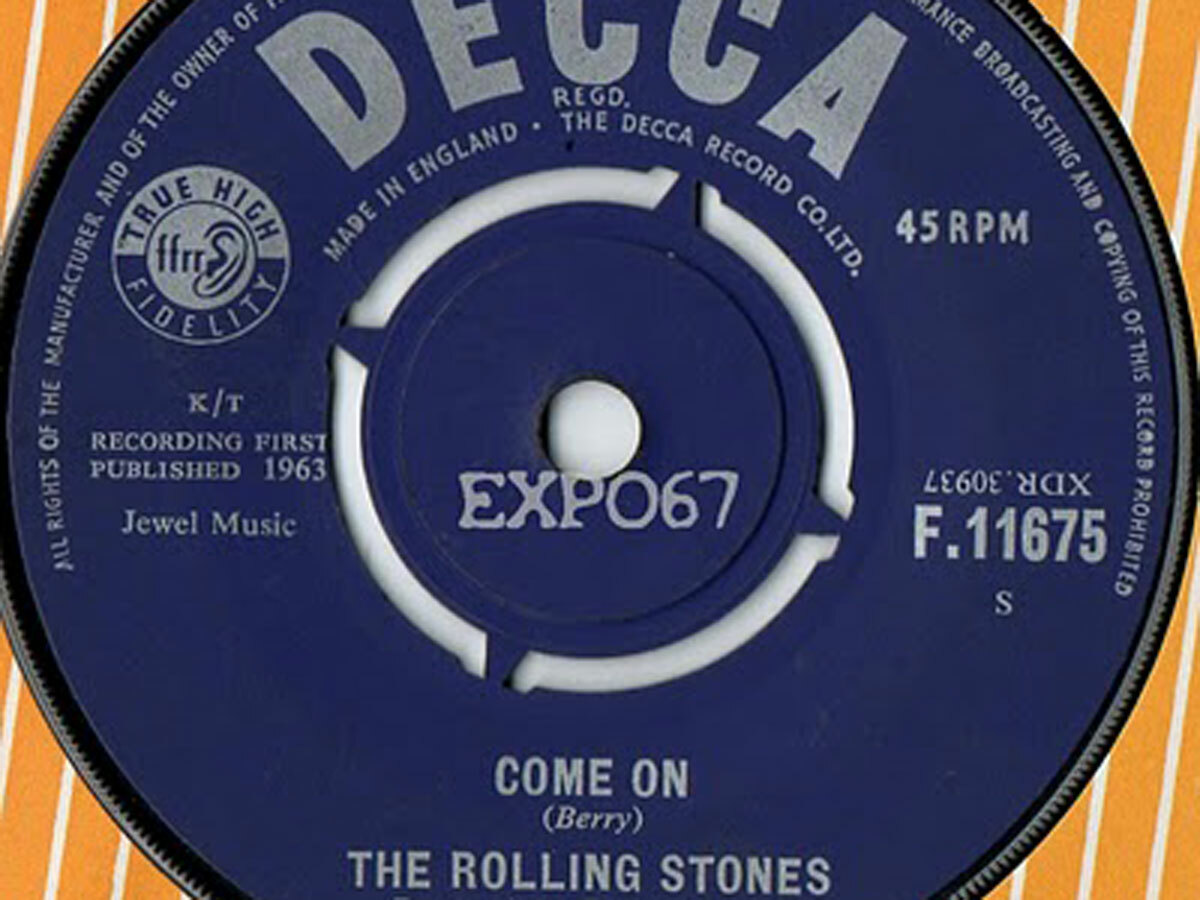

Key Stones Recording: The first Rolling Stones recordings didn’t even push the 3 minute barrier. Their début, the Chuck Berry cover Come On makes its excuses and leaves before two minutes are up. I Wanna Be Your Man is about the same length. Follow up ‘Not Fade Away’ fades away a few seconds sooner. It’s All Over Now was first UK Stones single to break the 3 minute barrier, fading away a hair before 3’30”.

The 33rpm LP

Heyday: 1950 – 1988

Technical description: The 33rpm ‘microgroove’ record was originally intended to replace multi-disc ‘albums’ of classical music spread across multiple 10” 78rpm discs. It took a little while for pop acts to work out that they could do something more than collect the previous year’s single releases on and LP. But once they did, pop music would change forever.

Cultural impact: The first pop album that was conceived as more than a collection of singles was the Beatles’ ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.’ Paul McCartney, disenchanted with the manic merry-go-round of single releases and Royal Command Performances dreamed up the idea of an imaginary band to play on the Beatles’ next record. The ‘concept’ collapsed before recording was finished and Sgt. Pepper mostly comprises songs that might have sat comfortably on its predecessors Revolver or Rubber Soul, framed by the title track and a reprise. But the precedent was set. The album-oriented ‘progressive’ music of the 1970s took its cue from McCartney’s ambition. Bands such as Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, Yes and Genesis barely bothered with singles at all. Songs sprawled out to fill a whole 20 minute side of the LP. In the case of arch-proggers Yes, one song was smeared across four sides of a double album. For most of the Seventies, the album was king, only to be toppled towards the end of the decade with the advent of Punk.

Key Stones Recording: Their Satanic Majesties Request was the Stones’ somewhat unfocused rejoinder to Sgt. Pepper. It isn’t regarded as a classic. But actually the 1966 Rolling Stones release Aftermath featured an attempt to challenge the 3 minute standard. Side one concludes with Goin’ Home, a meandering blues exploration that jogs along agreeably until about the 11 minute mark.

The 12” Single

Heyday: 1976 – Present

Technical description: The 12” was invented by accident. The first ’12-incher’ (actually a 10” disc) was cut in 1974 by engineer José Rodríguez so that DJ Tom Moulton could play out a rough mix of Al Downing’s I’ll Be Holding On to test crowd reaction. Cutting a single song on a an album-sized platter has a number of advantages for a DJ. First, it enables the cutting engineer to cut a deeper, louder groove. Second, it makes it mush easier to discern the different sections of a song from the appearance of the grooves. That helps a lot when you’re trying to drop the needle on a great drum break or instrumental section. Third, a big box of records makes you feel more like a proper DJ rather than someone who’s just turned up to a party with a box of T.Rex singles. Oh, and of course fourth it allows for longer playing time which is handy if the DJ needs to pop out of the booth for a wee.

Cultural impact: The 12” single helped create a club culture that persists to this day. It’s just about possible to imagine the late Seventies Disco scene without 12-inchers but the paradigm-shifting influence of Acid House depended almost entirely on twelve inch singles. And without Acid House we probably wouldn’t have half of the current Top 40.

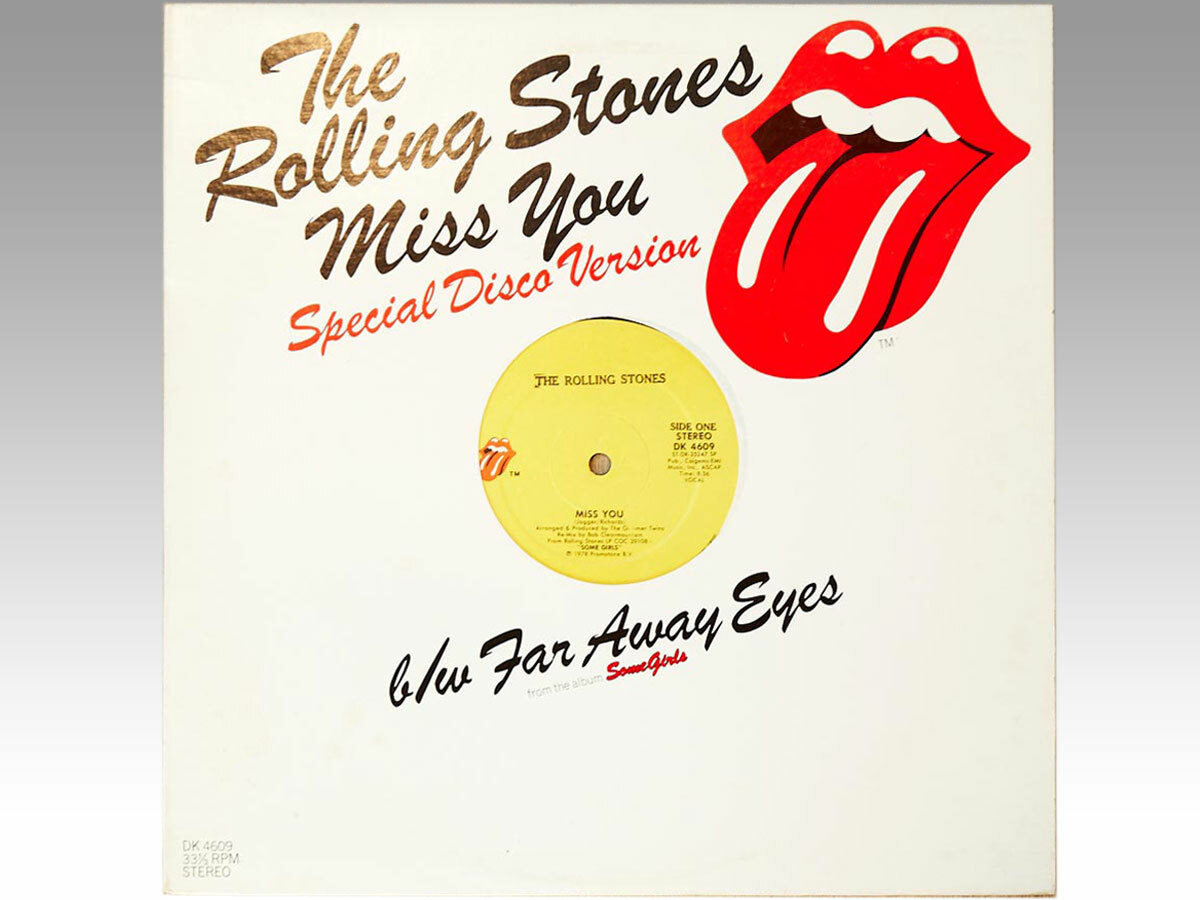

Key Stones Recording: The 12” “Special Disco Version,” of Miss You was the Stones’ first 12” single, and probably their best. It helped the song to the US Number 1 spot in May 1978 and was a turning point in the band’s career as they reinvented themselves in line with Mick’s espousal of the Studio 54 crowd.

The Compact Cassette

Heyday: 1979 − 1990

Technical description: The Compact Cassette is something of a poor relation to the LP, often considered an afterthought by marketing departments and artwork designers. The tiny box of magnetic tape reached its real peak long after its mid-Sixties introduction with the introduction of the Sony Stowaway…or, as it became known, the Walkman. In the Eighties cassettes were outselling vinyl records. So popular was the format that labels even started issuing singles on cassette. Remembered now because the word ‘mixtape’ — a home-made compilation of carefully-chosen songs — has entered the pop culture lexicon. Ironically just as the word ‘cassette’ has been deleted from the Oxford English Dictionary to make room for newer contenders.

Cultural impact: The real impact of the cassette was in the home taping arena. Crudely-assembled collections of favourites from the Top 40 recorded from the radio, romantic collections crafted by loving swains for their paramours, hope-filled demo collections destined for the snowdrift of tapes on an A&R man’s office floor: the cassette was all of these things and more.

Key Stones Recording: It’s hard to think of a Rolling Stones record that was shaped by the cassette medium. But it’s illuminating I think that when I researched this piece I could find a couple of Mick Jagger solo singles on cassette — for example 1993’s Rick Rubin produced ‘Sweet Thing’ — but no Rolling Stones cassingles. I don’t think Keith would allow anything so daft.

The Compact Disc

Heyday: 1985 − 2005

Technical description: The introduction of the CD represented a complete break with the lineage of the wax cylinder. Instead of a groove shaped with an analogue of vibrations in air the CD carries microscopic pits that are read as 16-bit, 44.1kHz digital information by a laser. The discs promised superior audio fidelity — which was certainly true on all but the most audiophile of systems — and near-indestructibility. Which wasn’t true at all. The pivotal CD recording was Dire Straits’ Brothers In Arms. A huge seller, it became the de facto demo disc for hi-fi shops and mini-system showoffs for the better part of a decade.

Cultural impact: One of the key things that the CD offered, in creative terms, was an embarrassment of running time. A vinyl album has room for about 40 minutes or so of audio. Much more and the cutting engineer’s job gets very tricky, and the resultant disc is underwhelmingly quiet. A CD can handle a shade under 80 minutes of audio. And of course if it’s there, artists feel pressured to fill it. Some songwriters have the kind of creativity that can cope with those vast digital vistas. Mick Jagger’s pal David Bowie, for example, came up with enough material to fill five vinyl albums in 1972 and ’73. Each one an acknowledged classic.

But not everyone has that much talent to spare – which is why a lot of CDs were padded with ‘bonus’ 12” mixes, skits, b-sides and other assorted that that should never really have seen the light of day. The high water mark for the bloated excess of the CD era was surely Guns N’ Roses’ simultaneous release of Use Your Illusion I and II in 1991 – a whopping two and a half hours of guitar solos, dolphin noises and orchestras.

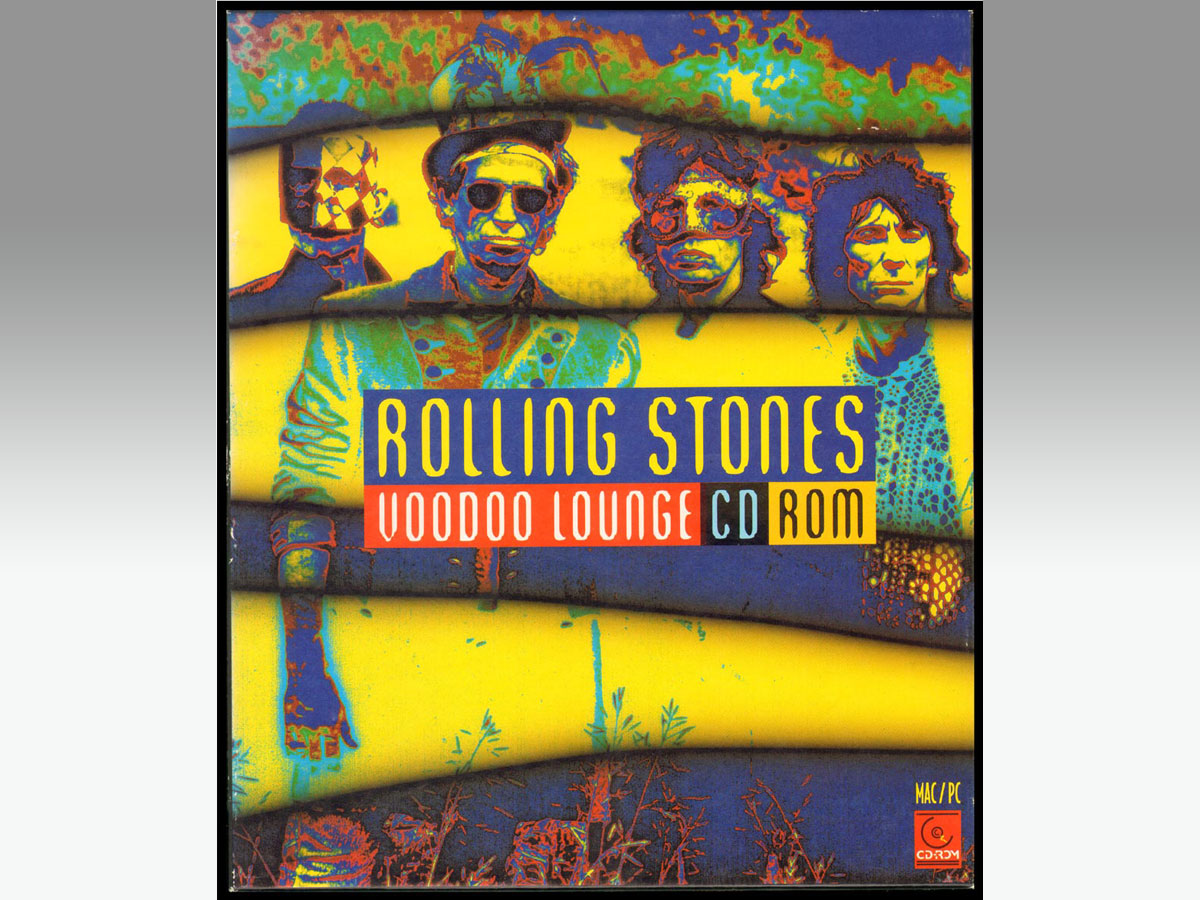

Key Stones Recording: The Rolling Stones were as prone as any to content inflation. Tattoo You, Undercover and Dirty Work — released between 1981 and 1986 — averaged a shade over 40 minutes each. Steel Wheels, from 1989, edged up to 53 minutes and their next three albums; Voodoo Lounge, Bridges To Babylon and A Bigger Bang, were all comfortably over an hour long. The dilution of their creative force hasn’t had an appreciable effect on chart placings but it’d be a devoted fan indeed that suggests the last three Stones records are the best ones. Voodoo Lounge, the band’s 1994 release, was followed a year later by an ‘enhanced’ CD-ROM version. It’s an initiative that a few bands have tried. None with conspicuous success.

Digital Downloads

Heyday: 2000 – Present

Technical description: Once a piece of audio has been digitised at sufficient quality, there’s really no reason for it to exist on a dedicated disc (or cylinder) at all. It can be delivered over the internet to whoever wants it as long as they’re willing to pay the price. Or, in many cases, even if they’re not. MP3s were originally small files — typically about 4MB per song as opposed to the 40MB of a CD-quality AIFF or WAV file — with brutal compression (down from 1411kbps to around 128) that made for a pretty grainy sound. With fast internet connections becoming increasingly common and large capacity hard disks getting cheaper all the time we’ve become much less careful with file size. A typical 320kbps MP3 or iTunes AAC for a 3-minute pop song can be upwards of 8MB; a ‘lossless’ FLAC file about 20MB; an uncompressed HD audio track at CD-slaying 24-bit, 96kHz quality at over 100MB.

Cultural impact: Digital downloads have done a lot more than eliminate the retail middle-man. The demise of high street record shops may be the most obvious sign of the digital revolution but there are myriad other changes too. Increasingly, with revenues falling (whether you blame illegal downloads, CDs that are too full of filler tracks or the ubiquity of Simon Cowell) record companies have tried to leverage 360 degree deals that take in concert revenues and merchandising as well as record sales. Bands such as the Arctic Monkeys used the simplicity of digital dissemination via social networks to score record deals; equally, acts that already have a profile are dispensing with the traditional record company and connecting with their fans directly. Downloads mean they don’t need a complex distribution network – just an office.

The likes of Jethro Tull are getting along fine as 21st century minstrels, selling their songs direct to the people that like them. Taking the long view, before Edison musicians earned their keep from live performances; in a few decades that – and merchandising – may be the principal revenue stream again. Indeed, forward-thinking acts like Nine Inch Nails are giving away their songs for free and selling increasingly elaborate deluxe editions of their albums, packaged with books, photos and other ephemera – a throwback to the days of Sgt. Pepper, where the packaging of the album was as much of an experience as the songs.

Key Stones Recording: Certainly the Rolling Stones touring operation has been their big money earner since the 1980s. Surprisingly, LSE educated business wizard Mick Jagger hasn’t (yet) taken the Stones catalogue in-house. Although the band was one of the first to set up a boutique ‘vanity’ label back in the Seventies. The Rolling Stones have released their entire catalog on iTunes as part of the band’s 50th anniversary celebration. Everything from 1963’s “Come On” to last year’s GRRR! compilation is now available for download. Interestingly, one of the purchase options is a ‘complete catalogue’ package that comes in two chunks, from 1961-1971 and 1971-2013.

Streaming Audio

Heyday: Now

Technical description: With ever-faster broadband and mobile internet, it’s a moot point whether anyone needs to ‘own’ music at all. Almost anything that strikes your fancy can be heard on demand through Spotify, Amazon Cloud Player, the fothcoming iTunes Radio or – somewhat comically – via a video of a 45rpm record being played on YouTube.

Cultural impact: In the future, this is probably how we will all listen to music. You probably do already, even if the quality’s not as good as your HD FLACs, as the endless choice means there’s no easier way to find new bands to love. The idea of someone having a record collection will soon seem as quaint as someone having a horse or a sword. Just as there are eccentrics today who ride horses to work or collect samurai swords, there will be always holdouts with libraries of slowly crumbling vinyl. But they’ll be a shrinking minority. The far future may sound weird and uncomfortable by the standards of those of us who grew up with the Rolling Stones. But most of us won’t have to live there.

Key Stones Recording: The Rolling Stones iPhone app is an example of the way that music delivery media might evolve in the future. The members of the band aren’t getting any younger, but the band as a corporate entity will probably endure through initiatives like the Rolling Stones app deep into their retirement. As Mick once sang: ‘Time Is On My Side.’