Tomb Raider Remastered: how Lara Croft changed gaming

As the first three titles in the long-running series get a remaster, we look at how the games influenced an entire industry

Tomb Raider has been ripe for a remake for some time. The most recent game to bear the name, Shadow of the Tomb Raider, came out in 2018, but in a series that dates back to 1996 and the glory days of the first PlayStation there’s a lot of great exploration and puzzle design that doesn’t deserve to be forgotten in the mists of history.

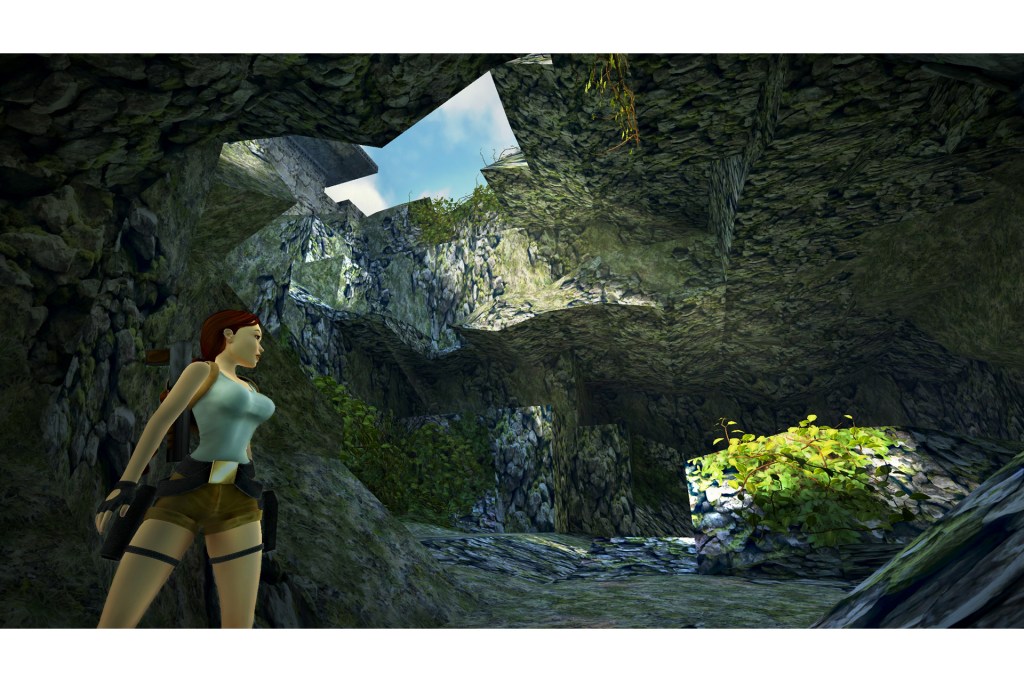

Luckily, we now have Tomb Raider I-III Remastered, Aspyr Media’s remake of the first three games in the series for modern consoles and PC. The three games included in the bundle include some of the greatest moments of the early 3D console era, such as the fight against the T-rex, being hunted by a shark, Croft Manor and acrobatic clambering over ancient ruins long before Nathan Drake had even untucked his T-shirt.

Tomb Raider was first imagined by Toby Gard and his team at Core Design in Derby, England, which was looking for a 3D title to develop for the PlayStation. At first it featured an Indiana Jones-like protagonist – a bit too similar to the LucasFilm legend, it turned out, and a redesign was requested to avoid copyright problems. Thus, Lara Croft was born, a British archaeologist who spends surprisingly little time drawing diagrams and sifting through loose dirt for tiny fragments of pottery, preferring to climb, leap and shoot her way through ruins that should probably be on some sort of protected monument list. You never see Alice Roberts with a pair of pistols, do you?

Character building

Croft has gone on to become an important figure who has transcended gaming into movies, played by both Angelina Jolie and Alicia Vikander. The very fact she was female played into PlayStation’s charge to liberate gaming from its stereotypical image of something enjoyed by kids, pasty nerds, but most of all young boys. WipeOut brought in a grown-up post-club crowd with its soundtrack of banging tunes, there were horror games that appeared in the likes of Spaced, and as Chun-Li mains had already violently proven in Street Fighter II, playing as a female character was in no way a bad thing, despite there being plenty of whinging to that effect from those who felt their already fragile masculinity was being further undermined by the mere presence of a woman in a mainstream game.

That said, there was one thing – or possibly two – about Croft that stood out. The rendering limitations of the PlayStation meant her figure was more polygonal than naturalistic, but this didn’t stop the marketing department from emphasising her sex appeal. She appeared on magazine covers, usually the domain of scantily clad models, sometimes in a Christine Keeler-like pose, in a bikini or on a bed with implied nudity. It didn’t always go down well with her creators. Speaking to the Guardian in 2006, around the time of Tomb Raider Legend’s release, Gard said: “She was always designed to look good – people’s psychology is that they like attractive characters [of] both sexes. What I objected to was the marketing which represented Lara in a way that was nothing like the character.”

There was, of course, a patch for the PC version that removed Lara’s clothes and revealed some unremarkable flesh-coloured polygons. Nude Raider resulted in a flurry of cease and desist letters from Eidos, and contrary to rumour was never baked into the game itself. A cheat code in Tomb Raider II was alleged to have a similar clothing removal effect, but instead blew Lara up.

Croft aloft

Croft character was originally based on singer Neneh Cherry and comic-book character Tank Girl, and was named Lara Cruz. The name was changed at the behest of publisher Eidos, and while there’s a story that Gard accidentally increased her breast size through a slip of the mouse, he has since put that down to “a silly remark made in an interview”. Tomb Raider Legend would retcon her origin story to add extra family trauma, and more recent games have tried to tone down her unreasonable proportions and introduce more realism, to the extent that a young, injured girl mowing down crowds of mercenaries with a bow and arrow in the 2013 game starts to look absurd, though perhaps no more than serial killer Nathan Drake moving in normal social circles.

Croft’s commercial appeal was key to the game’s initial success, and has stuck with her ever since. In a thirdperson game, with the character visible at all times, there’s less identification with the player. Firstperson protagonists, especially silent ones such as Gordon Freeman from Half-Life, invite the player to inhabit them, to fill the empty space behind the gun with their own thoughts, needs and motivations. Croft didn’t need that. In cutscenes as well as the game levels themselves, her character was a strong one.

In Gard’s Guardian interview, he addressed the character’s original design: “She was mysterious and had a danger about her; this gave her a real difference to other female characters that were basically sex objects. I was also very keen to get Lara to animate properly, which no one else at the time was doing. This made her move slowly but look realistic which helped players empathise with her.”

It helped that her adventures and treasure hunts often involved shooting wildlife and armed men, something gamers were conditioned to do, but the influence Tomb Raider had on the games that came after cannot be played down. Without Croft we’d have no Uncharted, no Syphon Filter, perhaps no Max Payne. Resident Evil 4 took thirdperson mechanics to a new level in 2005, moving the camera closer instead of Tomb Raider’s expansive views that were made to take in her environment to show potential routes up structures.

The other important thing is that Croft wasn’t – and continues not to be – a damsel in distress. Far from waiting for a plumber to rescue her, or acting purely as an object for a male character to ogle and flirt with, she took the fight to her enemies. That she arrived in 1996, the same year the Spice Girls released Wannabe and the words ‘girl power’ were everywhere in the media, was probably a coincidence unless you want to spin a conspiracy theory involving Sony, Eidos and Virgin Records, but it certainly didn’t do any harm.

Echoes through time

The remastered early games stand in contrast to the more recent releases because of their relative crudity and their presentation of Croft as a pure action hero. From 2013 onward we were expected to sympathise with the character as someone fighting her way up against stacked odds, the new survival mechanics making her feel vulnerable on her journey to a position of power. She felt like an ordinary girl, something that was also part of the character of Nathan Drake, who first appeared in 2007’s Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune. His creators at Naughty Dog imbued him with a lot of qualities taken from Indiana Jones and the protagonists of swashbuckling movies, yet kept his character grounded in the same way Croft was, by giving him a family connection, keeping his animation and abilities realistic, and allowing voice actor Nolan North to use improvised asides to bring out his personality.

Tomb Raider had a huge influence on the games that followed it, but retains its relevance today. The early games may seem coarse by today’s standards, all angular polygons and low-res textures, but two things stand out. The moments in the games themselves – whether it’s climbing ruins or shooting dinosaurs – remain as tightly scripted and action-packed as ever, and the character of Croft herself. They’re still well worth playing.

Read more

- Rule with an Iron Fist: how Tekken changed fighting games forever

- 25 of the best platform games ever

- Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown: the best Prince adventures across three decades