25 best movie CGI effects ever

From liquid metal killer robots to the very first CG animal, we take a look at some of the best eye-massaging visuals from the gates of Tinseltown

Stuff.tv recently visited visual effects house Industrial Light & Magic to find out how they conjure up virtual worlds on the silver screen – you can check out the full feature in the October issue of Stuff magazine, out now. Fired up with enthusiasm, we’ve decided to bring you the best computer generated visuals seen in movies. Note: we haven’t included full-length CGI animated features like Toy Story and WALL-E in the list. So without further ado, the 25 best movie CGI effects ever:

District 9 (2009)

Neill Blomkamp’s ET “invasion” movie didn’t move the CGI cheddar, but it did supply photorealistic exoskeletal aliens on a a shoestring budget of US$30m. The (non-special) effect was to open the SFX door to bedroom filmmakers, paving the way for Gareth Edwards’ Monsters (2010, shot for US$500,000) and Joe Cornish’s Attack the Block (2011, £9m).

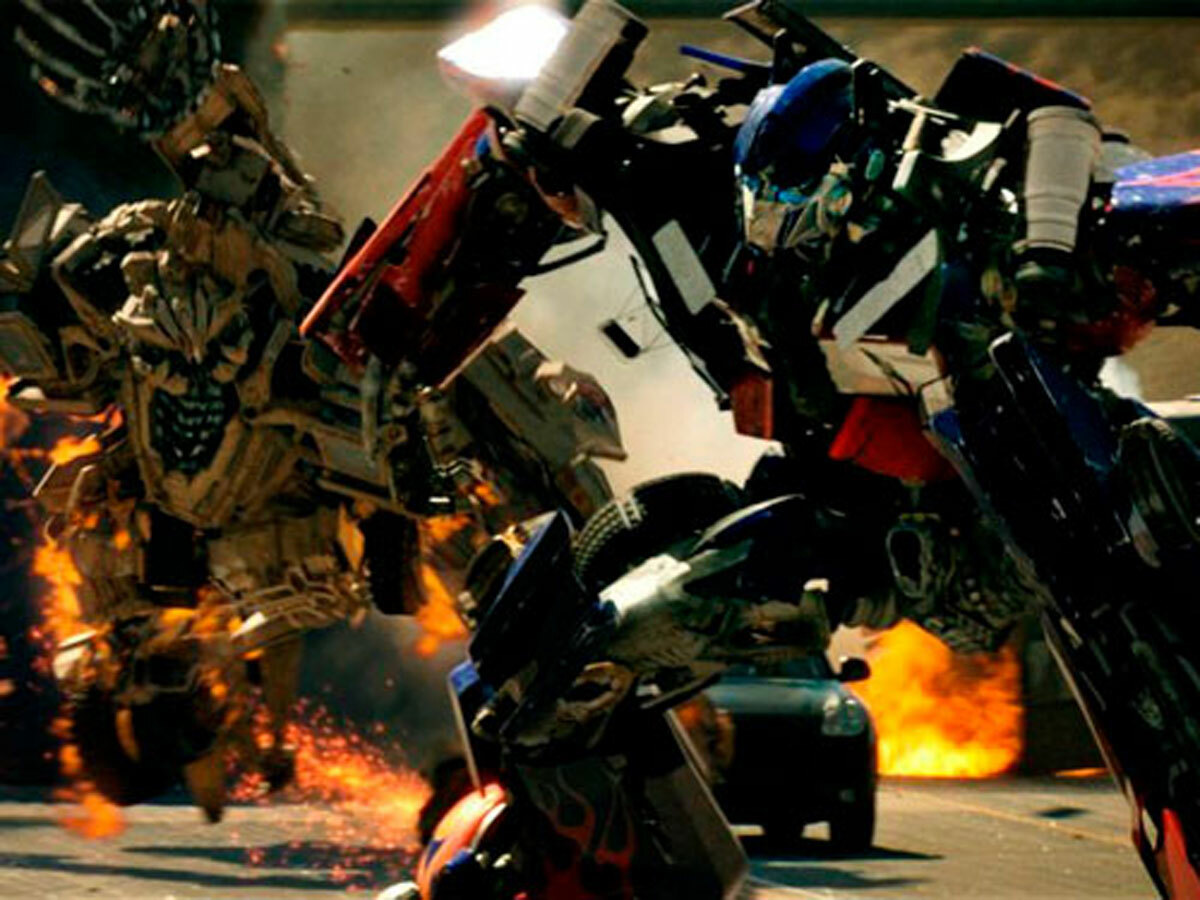

Transformers (2007)

Painstaking attention to detail was used to bring about on-the-fly transformations in meticulous detail. Optimus Prime comprised 10,000 individual parts; each frame taking Industrial Light & Magic a staggering 38 hours to render. But it was just a stepping stone to threequel Dark of the Moon’s Driller, which had more than 70,000 components. Shame about the plot.

Avatar (2009)

Scoff all you like at James Cameron’s box office-baiting blue people, but the innovative facial motion capture techniques required some serious tech – not least a Microsoft custom-built cloud asset management system and a 10,000 square foot server farm, managed by 35,000 processor cores. The final digital cut commanded over 17GB per minute, mocking your newfangled Blu-ray format’s pitiful 50GB capacity.

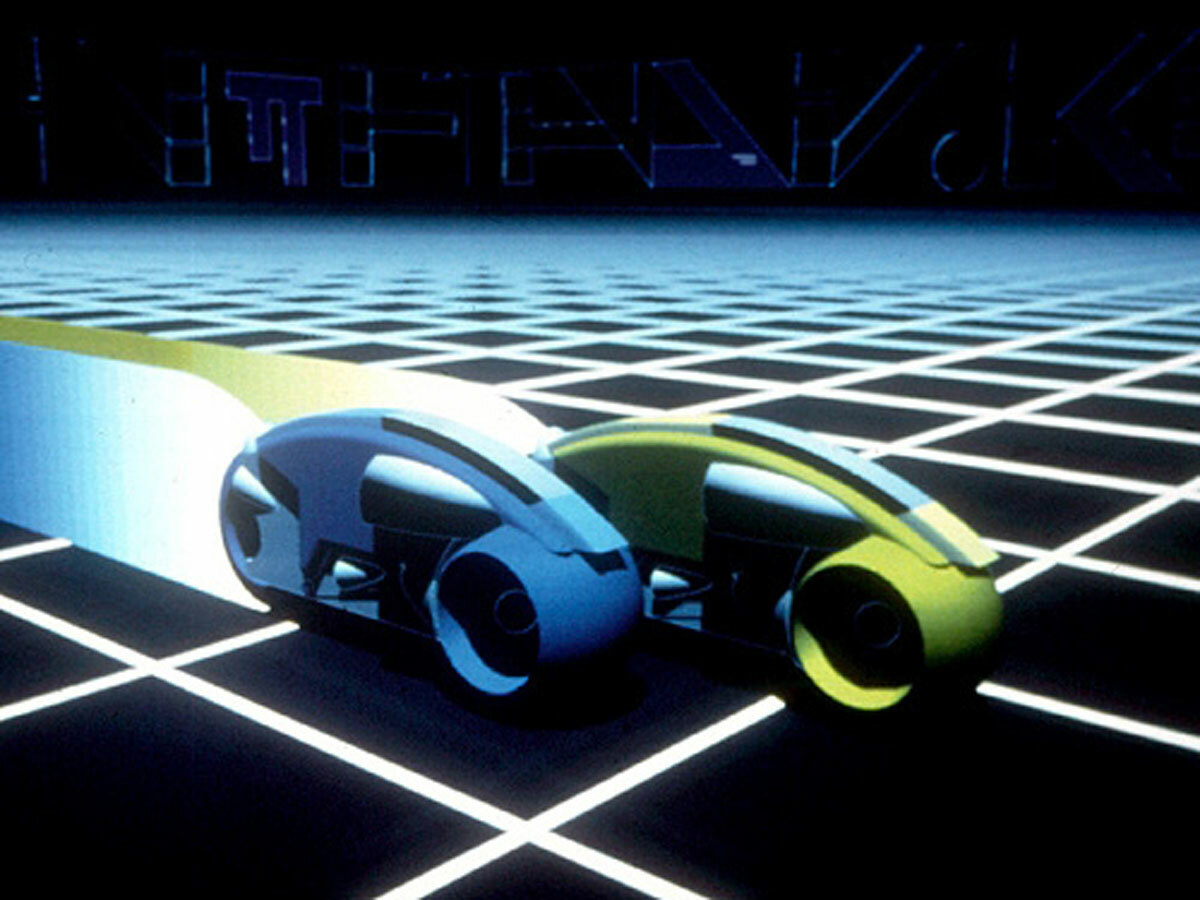

Tron (1982)

Considering the tech available at the time, it’s little surprise that only only around 20 minutes of CGI was created for Tron. The computer used to create those iconic scenes had 2MB (yes, that’s an M) RAM and not more than 330MB of storage. Then again, that was enough to create the light-cycles – and a classic portion of sci-fi that 2010’s US$170m Tron:Legacy could only dream of looking up to.

Gladiator (2000)

Ridley Scott’s epic may have looked like it was scribed on wax tablets and filmed by men wearing sandals, but it was Brit CGI post-production house The Mill who added tigers to the fights and created 35,000-strong crowds using a couple of thousand extras. Oh, and when Oliver Reed croaked it mid-production, they got around the problem by placing a 3D CGI mask of the late thespian on a stand-in for some scenes.

The Matrix (1999)

Although more famous for its bullet-time photography which, while impressive, owes nothing to the wonders of CGI, The Matrix combined digital effects with its innovative shooting style to great effect. Our personal favourite is the glass ripple effect of a slo-mo helicopter crashing into the side of a skyscraper.

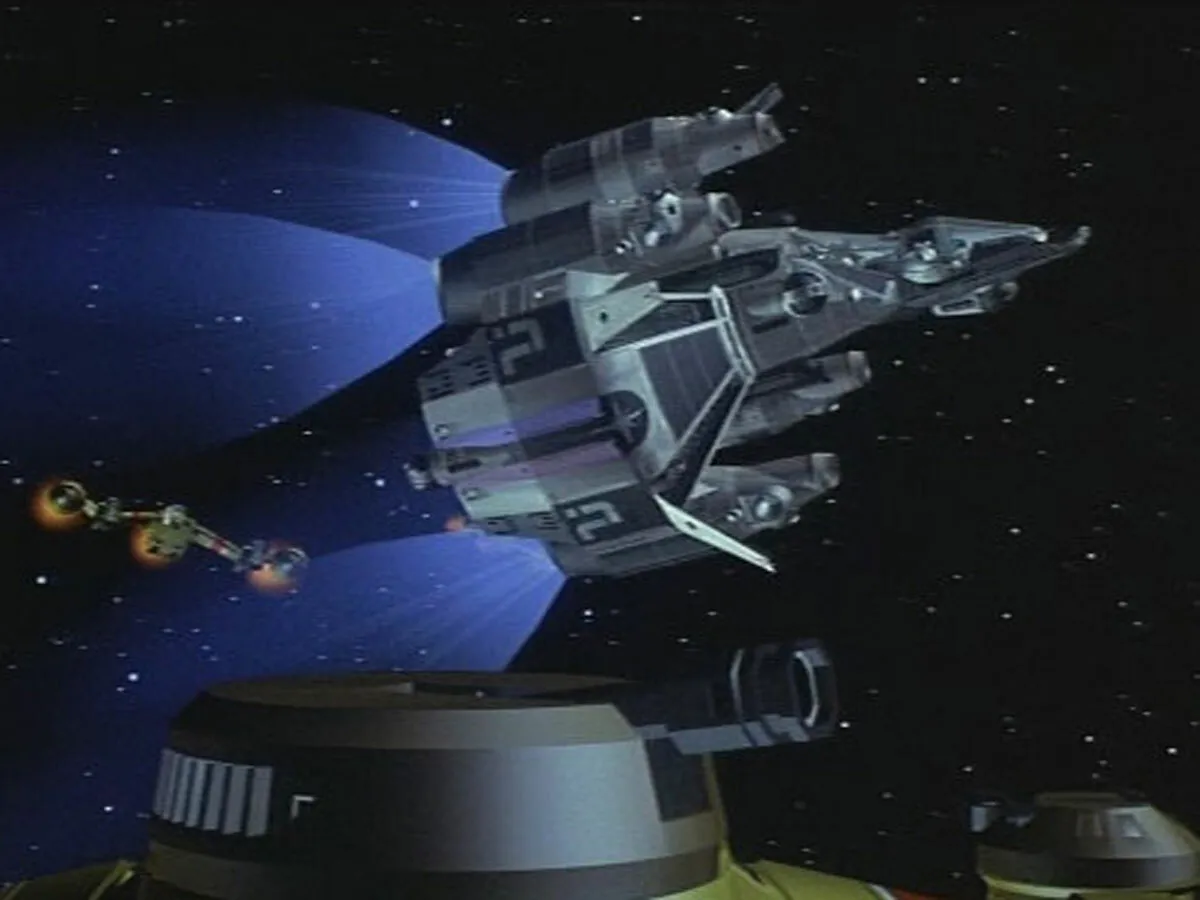

The Last Starfighter (1984)

This outer space adventure about a young gamer being recruited to fight in a real galactic war featured a plethora of CGI effects shots – rather appropriately. All the shots of spacecraft, the space itself, and the ensuing battles were generated on a Cray X-MP computer. Playground rumour had it that Atari built a real Last Starfighter machine which was never put into production. We can but hope.

Spider-Man 3 (2007)

Spider-Man 3 featured 900 visual effects shots that meant creating brand new computer programs that didn’t exist before the film began shooting. The most impressive scene sees super-villain Sandman forming from thousands of individual grains of sand. A breathtaking sequence, both as a technical feat and for the pathos that director Sam Raimi brought to the character’s origin.

Hollow Man (2000)

Inspired by the H. G. Wells Invisible Man this Kevin Bacon staring take on the classic was nominated for an Academy Award for Visual Effects – but lost to Gladiator. The scene most notable was when Bacon’s character became invisible and vanished a layer at a time from skin to muscles to veins and then bones. Apparently this scene employed a fancy shader that used volumetric hypertexture shader and 3D procedural noise to peel layers off – pretty standard really.

Westworld (1973)

Westworld saw whe first use of 2D digital imagery in the cinema, for the point-of-view shots from Yul Brynner’s robot gunslinger. It was pretty primitive – using 2D animation with raster graphics, or dot matrix to you and I – but from small acorns mighty CGI oaks would eventually grow.

Jurassic Park (1993)

Agh, it’s a dinosaur! That was our reaction when first watching the jaw-dropping effects of the T-Rex, which took six hours per frame to render. Of course that was coupled with the first outing of Dolby Digital Sound in theatres which made for an ear-bleedingly real experience.

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982)

The first-ever entirely CGI sequence seen on film – Star Trek II’s Genesis Effect – was created by the Lucasfilm Computer Graphics Division, which later went on to become the Pixar we know and love today. Although it didn’t feature in the film as a representation of reality – instead turning up in a glorified PowerPoint presentation – it’s still pretty impressive even today.

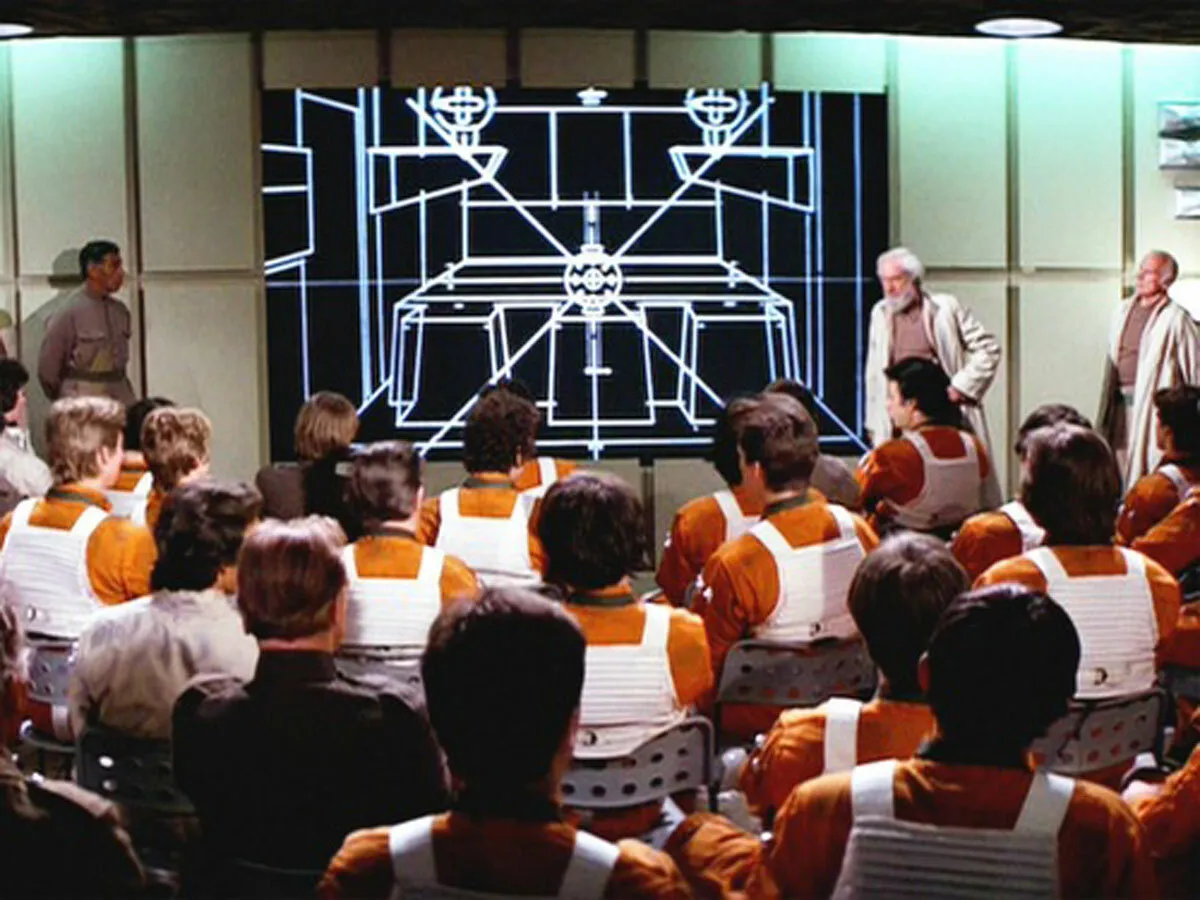

Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (1977)

Long before Jar Jar Binks, George Lucas was pioneering CGI technology. Back when it was still called plain old Star Wars, the first instalment of Lucas’ space opera saw the very first usage of 3G CGI on the silver screen. Larry Cuba’s computer schematic of the Death Star (which took months of programming) was used to create the 40 second animation of the Death Star trench in the briefing sequence. All together now: “You’re required to maneuver straight down this trench…”

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002)

Andy Serkis’ stunning performance as the wretched creature Gollum in Tolkien’s on-screen masterpiece was recorded with the magic of motion capture technology. Each scene with him had to be recorded three times – once with him wearing a skin-tight white suit, once with him speaking off camera, and finally by himself in a motion capture studio. He’s set to reprise the role in this year’s The Hobbit: There and Back Again. Hopefully he hasn’t forgotten how to do the voice, precious.

Starship Troopers (1997)

Starship Troopers’ epic CGI battle sequences help to explain its US$100 million dollar budget. Nominated for a 1997 Best Visual Effects Oscar, the large-scale bug-infested battle paved the way for the likes of the Battle of Pelennor Fields in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Return of The King.

Labyrinth (1986)

CGI Owls were gracing our screens long before they were resigned to delivering letters to budding witches and wizards in Harry Potter. Take the opening credits of Labyrinth for example, where a fully computer generated owl took the trophy for the first ever realistic CG animal seen in a film.

The Abyss (1989)

The infamous water snake effect from James Cameron’s underwater adventure was created using an early version of Photoshop – then unreleased to the public. The programme was created by Thomas Knoll, brother of ILM employee John Knoll.

Looker (1981)

Looker featured the first CGI human to appear on our screens – an honour bestowed upon Susan Dey of The Partridge Family. The first use of shaded CGI, Dey’s digitzation was portrayed by a computer-generated simulation of her body being scanned. Quite an honour indeed.

Young Sherlock Holmes (1985)

The first completely computer-generated character to feature in a film is, appropriately enough, an illusion – a stained-glass man hallucinated by an elderly priest when he’s shot by a poison dart. It took Industrial Light & Magic animator John Lasseter and his team four months to create the stained-glass knight – Lasseter, of course, later went on to found Pixar.

Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991)

James Cameron’s well-known for pioneering special effects technology – and in Terminator 2, he conjured up the most advanced computer generated character then seen on the big screen in the form of the T-1000. The liquid-metal assassin used every CGI trick in the book, including morphing effects, CG animation and reflections on its chrome surface – plus a few old-school practical effects to help sell the reality of the character. Audiences in 1991 were wowed by the digital creation as it morphed from one character to another, emerged from a tiled floor and formed knives from its hands.

Willow (1988)

Ron Howard’s fantasy adventure movie saw the first instance of digital morphing techniques on film, as Willow attempts to restore the sorceress Fin Raziel to human form. It looks laughably quaint now – you can perform similar tricks in real time on your smartphone – but at the time, the fluid shift between ostrich, tortoise, tiger and woman was mind-boggling.

The Day After Tomorrow (2004)

Water’s always been a tricky thing to get right on screen – witness all those ropey old model shots of ships, where the water doesn’t scale properly – but CGI’s made it possible to create realistic shots of water on a grand scale. A case in point is the flooding of Manhattan in eco-disaster movie The Day After Tomorrow – which called on Digital Domain to conjure up a tidal wave of water that accurately flowed through the streets of New York. The film itself was more of a damp squib.

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008)

David Fincher’s bass-ackwards biography called for Brad Pitt to play the title character from his birth as an old man to his twilight years as a youngster. The CGI effects team from Digital Domain had to create a CGI lead character that would mirror Pitt’s performance and hold up to scrutiny – for the first hour of the film. No small challenge – but they rose to it, capturing Pitt’s performance and mapping it onto an anatomically-accurate maquette of the aged Benjamin Button – and then placing the resulting CGI creation onto the bodies of different actors who played Pitt at different ages. Check out how Digital Domain realised the effect in this TED talk.

Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006)

To realise the outlandish half-man, half-fish crew of The Flying Dutchman, Industrial Light & Magic refined its motion capture tech into the iMoCap system. Actors performing motion captured roles could work opposite their colleagues on-set – meaning that ILM could include more elements of Bill Nighy’s performance as the half-squid Davy Jones into the CGI character that appeared on-screen.

Death Becomes Her (1992)

This somewhat forgettable horror-comedy bagged Industrial Light & Magic a visual effects Oscar for its work. It pioneered the depiction of realistic human skin using CGI – used to great effect in twisting Meryl Streep’s head around on its neck and punching a hole through Goldie Hawn.